Undocumented immigrants see glimmer of hope in 2012

By Patricia Zapor

Catholic News Service

WASHINGTON (CNS) — For the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S., 2012 brought glimmers of hope that there might soon be a way to clear up their unsettled legal status.

After nearly two decades of stymied efforts to fix what is widely acknowledged to be a broken U.S. immigration system, two things in particular gave a sense of optimism to undocumented immigrants, their families and advocates.

First, the administration launched a stopgap program to defer deportation and give work permits to certain young adults, perhaps as many as 1.8 million of them. Then, election results showed President Barack Obama and other Democrats had a huge advantage among Latino voters, leading to bipartisan talk of comprehensive immigration reform.

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, known as DACA, as of mid-November had given more than 53,000 young adults the chance to work legally while knowing that the government was officially not going to try to deport them, as long as they continue to meet the requirements.

The program announced in June and launched in August applies to people younger than 31 who arrived in the U.S. before their 16th birthday, have been here at least five years, have clean criminal records, have completed or are enrolled in school and who were in the United States as of June 15.

The application and its required fingerprinting costs $360. Approved applicants can obtain a Social Security card and receive a work permit. The approvals are valid for two years and can be renewed.

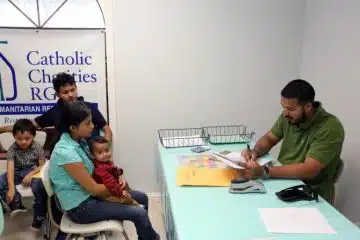

Catholic immigration programs around the country teamed up with other organizations to offer training in processing the applications as soon as it launched, then began hosting educational programs for potential applicants and workshops for completing the paperwork.

According to the most recent statistics available, more than 300,000 people had applied by Nov. 15, and most of those were somewhere in the process, either awaiting their fingerprinting appointments or adjudication of their applications. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the agency in charge of the program, said about 10,000 applications had been rejected.

When he announced the program, under the authority given the government for prosecutorial discretion, Obama said, “it makes no sense to expel talented young people who for all intents and purposes are American.” The new policy will make the system “more fair, more efficient and more just,” he said.

But it’s not intended to be a permanent program, Obama said. “This is not amnesty, this is not immunity, this is not a path to citizenship; this is not a permanent fix. It is a temporary stopgap measure that allows us to focus our resources.”

The program was likened to a watered-down version of the DREAM Act, the acronym for Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors, a long-standing congressional effort to give legal status to young adults who were in the United States through no fault of their own, many of whom grew up in the United States and have no real connections to their homelands.

Their undocumented status makes it illegal to hold paying jobs and prevents many from going on to college because they’re not eligible for government-funded loans and grants. Some jurisdictions also require legal U.S. residency before someone may obtain lower in-state tuition rates.

The DREAM Act has long enjoyed bipartisan support and was backed by President George W. Bush, but it has never managed to pass through both houses of Congress. During the presidential campaign, the differences between Obama and Republican nominee Mitt Romney on the topic of immigration reform became sharp.

Following the lead of some in the Republican Party, Romney said undocumented immigrants should be encouraged to “self-deport” by making life difficult for them with laws such as those passed in Alabama, Georgia and Arizona. Among provisions of those states’ laws — some of which have been blocked by courts — are those requiring proof of legal status to get utility service or rental contracts, for instance.

Obama won the Nov. 6 election with more than 71 percent of the Latino vote, in a year with the highest turnout ever of Hispanic voters percentage-wise; they accounted for 10 percent of all voters.

Hopes rose of passing the DREAM Act and other components of what is generally called comprehensive immigration reform. The term is used to include a path to legal status and citizenship for undocumented people; many more visas for temporary, low-skilled workers; an easier, quicker route to family reunification; and border security.

Before election week was out, Republican leaders were acknowledging the role Hispanic voters played in the outcome and saying the time had come to pass comprehensive immigration reform.

The advocacy community that has long included representatives of various churches, particularly the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Catholic Charities USA and numerous religious orders, have been rallying support and meeting with White House and congressional leaders in hopes of drafting legislation that can begin moving through Congress early in 2013.

At a Dec. 4 news conference that preceded a daylong strategy session for national leaders, Bishop Jaime Soto of Sacramento, Calif., said whether legislation gets through Congress in one piece or as a series of bills is less important than that the broad goals are accomplished.

“This is a humanitarian issue with moral implications,” said the bishop, chairman of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Committee on Cultural Diversity. “We can no longer accept the work of undocumented immigrants while scapegoating them.”

The goal of comprehensive reform, according to Bishop Soto, is “making families, as well as all of America, whole again.”