The Banquet of Heavenly Grace in “Babette’s Feast”

Isaiah 25:6 is perhaps the keynote scriptural passage accounting for Heaven as a great banquet: “On this mountain, the Lord of hosts will provide for all peoples a feast of juicy, rich food and pure, choice wines,” declares the prophet. Isaiah associates this feast with the reconciliation and salvation of all people. The Lord “will destroy the veil that veils all peoples, the web that is woven over all nations; he will destroy death forever” (Is 25:7).

Isak Dinesen’s 1958 short story “Babette’s Feast” is, among other things, a wonderful, fictional interpretation of Isaiah’s great prophecy. Later made into an Oscar-winning film by director Gabriel Axel, Dinesen’s tale uses food as a metaphor of reconciliation, redemption and heavenly joy.

The story begins by describing a little Lutheran cult centered on an authoritarian and manipulative minister in a tiny, isolated mid-19th century coastal Norwegian village (the film moves the setting to Dinesen’s native Denmark). The pastor, whose wife has long since died, is assisted by his beautiful, young adult daughters in ministering to his small, devoted congregation. Both sisters were courted by dashing and romantic visitors to the town—one a soldier, the other a famous opera singer—but their father selfishly schemed to drive both away, leaving the daughters free to serve his whims and the demands of his aging and dwindling flock of followers.

This Lutheran sect renounced all worldly pleasure because “the earth and all that it held to them was but a kind of illusion,” choosing an austere diet solely for sustenance, never enjoyment or savor. “Luxurious fare was sinful,” the sisters explained. Food “must be as plain as possible; it was soup-pails and baskets for their poor that signified.” Their diet consisted of salted, dried fish and tasteless gruel, which matched their lives’ meager asceticism. The sisters “had never possessed any article of fashion; they had dressed demurely in gray or black.”

On a rainy night in 1871, long after their father died, the sisters found at their door a “deadly pale woman … who stared at them, took a step forward and fell down on the doorstep in a dead swoon.” When revived, she pulled a letter from her pocket from one of the sister’s former suitors. The letter introduced “Madame Babette Hersant,” who, being on the wrong side of the political aisle, fled Paris in the midst of civil war. Her husband and son, the letter explained, had been shot. She barely escaped, with nothing other than the clothes she wore, and could not return to France. Would the sisters take her in as a servant or housemaid? As an afterthought the letter added, “Babette can cook.” When the sisters explained they could only afford their one, young servant, Babette said she would serve them “for nothing, and … would take service with nobody else.”

The sisters “trembled a little … at the idea of receiving a Papist under their roof.” But they “silently agreed that the example of a good Lutheran life would be the means of converting their servant” and took Babette in. However, they distrusted the letter’s assertion that she could cook. “In France, they knew, people ate frogs.” So, they taught her how to make the staple meal they prepared daily for themselves and their father’s dwindling flock of disciples: split cod and a thick, tasteless dish of “ale-and-bread-soup.”

As soon as Babette took over cooking, the community “felt a happy change” in the sisters and “thanked God for the speechless stranger, the dark Martha in the house of their two fair Marys.” However, the dozen or so disciples fell into discord and bitterness, quarreling among themselves, bringing up past venial and grave grievances and threatening recriminations. This was occurring as the centenary of the founding minister’s birth was quickly approaching, leaving the sisters in despair about their father’s legacy. Babette then won a lottery in France, from a ticket an old friend had renewed for her year after year. Assuming this would be Babette’s ticket out of the increasingly querulous village and realizing they were too old to care for the little congregation, the sisters were thrown into despondency.

But Babette begged the sisters to allow her to cook a celebration dinner for the anniversary of their father’s birth and to purchase the ingredients with her lottery winnings. After some initial protest, the sisters allowed Babette to finance and cook the feast.

And what a feast it was! Having spent her entire winnings on the preparation, Babette lavished her guests with extravagant generosity, delivered by the richest foods and finest wines. Each sumptuous dish was a sign of Babette’s gratuitous love and illustrated God’s infinite grace. As they ate, the little flock repented of their petty grievances and grudges, offering and granting forgiveness and reconciliation to one another. Babette exemplified the grace that accompanies selfless hospitality, often communicated by surprising means.

And thus does Babette’s feast return us to Isaiah 25, in which heaven is described as “a feast of juicy, rich food and pure, choice wines.” Babette did not merely feed the flock’s appetites; she fed their souls. Food was not the end; it was the means by which God’s grace was mediated through his generous servant.

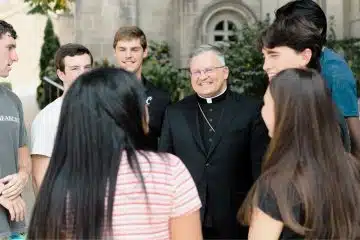

Dr. Kenneth Craycraft is an attorney and the James J. Gardner Family Chair of Moral Theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology.

Dr. Kenneth Craycraft is an attorney and the James J. Gardner Family Chair of Moral Theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology.

This article appeared in the June 2023 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.