The Ancestral Name Game

Names are a significant part of an individual’s identity, embodying personality, religious and cultural roots, and family background. Naming is one of the great privileges given to Adam in the Garden of Eden. “Genesis” means “beginning.” The first book of the Bible is a book of origins, and there are many stories where people’s names are rooted in how they began. During Biblical times, a first name was sufficient. As the population grew, a surname was needed and ultimately required.

In earlier civilizations, man was identified by his occupation. The development of surnames and their universal use followed commerce, so that countries involved in trade were the first to use surnames. Last names can be derived from occupations (e.g., Carpenter), locations (e.g., Field), personal characteristics or nicknames (e.g., Small) or paternal lineage (e.g., Johnson). In some cultures, surnames were assigned based on the father’s name (e.g., Fitzgerald, meaning son of Gerald). Over time these naming practices were influenced by historical, cultural and linguistic factors. Records we use for research are church, civil and census, as well as wills.

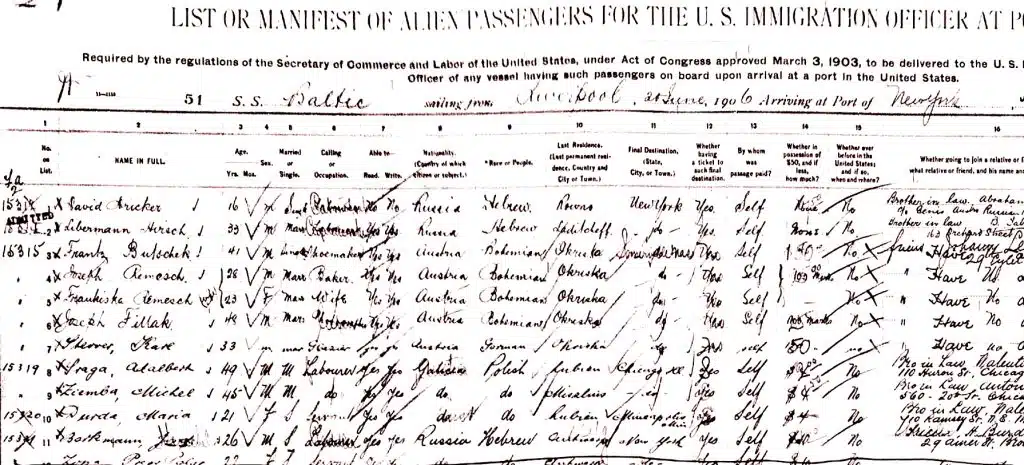

There is a prevalent myth that family names were changed by inspectors at Ellis Island—but this is unlikely. The clerks at Ellis Island didn’t write down names; they worked from lists created by shipping companies. An immigrant bought a ticket from an office near his home, so the seller most likely spoke the same language and transcribed the name correctly. In cases where the name was recorded incorrectly, it had been transcribed incorrectly.

However, name changes were often made by the immigrants themselves. Most immigrants traveled to the U.S. for work, and employers preferred workers who were somewhat “Americanized.” If an employer thought the potential employee’s name was too difficult to pronounce, the employee might be called by a nickname, and the new name was then used for everything else.

Other immigrants might have opted for a name that was easier to spell. Illiteracy played a role in last name misspellings. Often, the only written records were recorded by others, such as an enumerator taking a census, who would spell it as he heard it pronounced. This led to names with different spellings that are all phonetically similar. Such changes are especially common in immigration records when there are additional factors, such as language barriers. Fortunately, there are tools that can help overcome spelling differences.

SOUNDEX

The Soundex Code is an algorithm invented by Robert Russell in 1918. It is a phonetic index that groups names that sound alike but are spelled differently, such as Stewart and Stuart. Searching by Soundex variations can find records despite spelling differences (such as “Smythe” for “Smith”) or errors (such as “Synder for Snider”). Every Soundex Code consists of a letter and three numbers. It is a great tool, but be aware it is not perfect. For more information and examples, please visit: https://www.archives.gov/research/census/soundex

Genealogists can also use wildcard operators to discover new family details. An asterisk (*) can help find missing letters, search for middle names or initials, or even missing text strings. The question mark (?) can help find alternate spellings of a name. For more information on how to use wildcards, visit https://support.ancestry.com/s/article/Searching-with-Wild-Cards?language=en_US

Using Boolean operators enables precise search options. Use AND to expand a search, OR to introduce options and NOT to exclude information. This is a great tool when researching old newspapers, such as The Catholic Telegraph for marriage bans as far back as October 22, 1831. (Watch for more information in an upcoming issue.)

When researching first names, one’s culture usually determines the naming pattern of first names. For example, in some areas it was common to name the first son after the father’s father, the second son after the mother’s father, etc. A well-known practice in many Catholic European cultures was to give the newborn the name of a saint. The child might be born on the saint’s feast day or where the saint is a patron, or the saint might be special to the family.

Names with saintly origins can provide clues to possible birth dates, special family affiliations and religious beliefs.

When Africans were enslaved and brought to America, identifiers that could tie them to their homeland or families were broken. Naming, particularly after emancipation, was a complex matter influenced by newfound agency, and the reasons behind choosing a particular surname varied. Once African Americans gained their freedom from enslavement, they also gained the freedom to name themselves and their children. (Look for more information in an upcoming article.)

NEXT UP: How to access the Archdiocese of Cincinnati’s Archives and Sacramental Records

Ruthy Trusler is a communication consultant with a passion for genealogy. For over 20 years, she has helped families document their ancestry and write their family legacies.

Ruthy Trusler is a communication consultant with a passion for genealogy. For over 20 years, she has helped families document their ancestry and write their family legacies.

This article appeared in the June 2024 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.