Suffering with the Black Madonna

In a visually saturated world, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed and become desensitized to beauty. Visio Divina, Latin for “divine seeing,” encourages us to slow down and engage in visual contemplation, using art as a profound tool for connecting with the Divine.

A Guide to Visio Divina

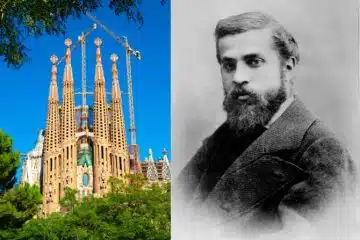

Begin by making the sign of the cross and inviting the Holy Spirit to guide your contemplation. Take a moment to meditate on the image of The Holy Virgin of Częstochowa. This piece is one of the many replicas of the original Our Lady of Częstochowa in Poland. This version, created sometime after 1714, resides in Radomysl Castle in Ukraine. Its exact origins remain unknown. The original image is adorned with a metal oklad covering, which serves as daily protection from pilgrims and the environment. In this version, the metal covering is captured through paint.

About the Original Image

While legends surround Our Lady of Częstochowa—including claims that it was painted by St. Luke and passed through the hands of St. Helena and Emperor Constantine—art historians theorize it was likely a Byzantine icon created between the sixth and ninth centuries. It became a symbol of protection and hope at the Jasna Gora Monastery in Poland in the 14th century. During its time there, the image survived wars and invasions, including a 1430 attack where it was slashed by a thief ’s sword. According to legend, the thief was struck dead by lightning immediately afterwards. The Black Madonna’s dark skin is attributed to candle soot and age affecting the wooden panel on which it was painted.

Enter in.

A dark-skinned Mary, adorned with jewels and gold, stands at the center, cradling her Son. Both Mother and Child are bejeweled with golden fleur-de-lis motifs, while angels support their crowns, exalting them as true royalty: Mary as Queen of Heaven and Jesus as King of Kings. The intricate details of Mary’s garment reflect a feminine power with delicate floral, star and diamond ornaments, reminiscent of her mantle in the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Below her hand, tears envelop a crowned sun—subtle, yet deeply symbolic. Jesus’ rich, blood- red robe, embellished with golden florals and crosses, draws attention to His sacrifice and kingship.

Notice the gold detail behind Mother and Child. What stories do you see illustrated here? In the top left-hand corner, a vulnerable Jesus is surrounded by men pulling on His robe from all directions. Their hands grasp greedily as they yell and fight over the fabric. These are the Roman soldiers tasked with crucifying Jesus, as they strip Him and prepare to cast lots on His garments.

On the top right is a peculiar depiction of the Annunciation. The Angel Gabriel flies over a kneeling Mary, delivering a pelican biting a snake. In medieval symbolism, it was believed that the pelican would pierce its own flesh to feed its young with its blood, representing Christ’s sacrificial love and the Eucharist. Gabriel is not offering Mary evil with the snake, but rather is demonstrating that through Mary’s fiat, the salvation of humanity has already begun.

Moving down to the left, we see Mary bowing before Jesus in the manger. Above them, an angel perches on a stable-like structure and is ornamented with chain and blood-drop motifs. This is the Nativity but, once again, paradoxical imagery appears within a joyful scene. The presence of the chains and blood foreshadow Christ’s Passion, symbolizing that through His sacrifice, the chains of sin and death will be broken.

To the right, men raise their arms around a haloed figure near a pillar—the Scourging at the Pillar. Just below this, near the infant Jesus’ shoulder, the Resurrected Christ steps from the tomb toward a castle turret, likely Jerusalem.

Focus on Mary’s face. Though serious, there is a gentleness about her. Her eyes are large, softly gazing at the viewer. Her nose is long and slender, and her mouth is small and pursed. These Byzantine features signify that Mary’s senses experience the supernatural as she reigns in Heaven. Her complexion is beautifully black, bringing to mind the verse from the Song of Songs: “I am black and beautiful” (Song 1:5).

Reflect.

There have been multiple efforts to buff out the scars of the original image in Poland, but miraculously, they reappear every time. Perhaps our Lady does not want us to erase her marks of suffering. Instead, she invites us into her suffering—the pain of her physical scars and the joyful and sorrowful memories displayed behind her. She reminds us, “You do not have to suffer alone,” and gestures to her Son cradled in her arms. “He is the Way,” she tells us.

Her beauty has drawn countless pilgrims for centuries, offering many graces to all who contemplate her. Her physical depiction transcends time, race and cultural boundaries. She stands in solidarity with all who suffer—the poor, the vulnerable, the marginalized—offering her shared pain and hope in her Son. She is our Mother, the Mother of all.

You can find a copy of the original icon (without the oklad) in our Cathedral Basilica of St. Peter in Chains in downtown Cincinnati. It was a gift from Karol Wojtyla, before he became Pope John Paul II, when he visited Cincinnati in 1976.

Emma Cassani is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph. She is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith. | [email protected]

Emma Cassani is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph. She is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith. | [email protected]

This article appeared in the November 2024 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here