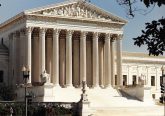

US Supreme Court: government agents violating religious liberty liable for monetary damages

By Kevin J. Jones

Denver Newsroom, Dec 11, 2020 / 05:02 pm MT (CNA).- Three Muslims who claim the FBI wrongly pressured them into becoming informants on Muslim communities may seek monetary damages as part of their lawsuit under a federal religious freedom law, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled in a decision that strengthens legal action on religious freedom problems.

“This unanimous decision from the Supreme Court makes it clear that government actors have to take religious freedom seriously—they can’t change their tune and then avoid the consequences of their previous bad behavior,” Lori Windham, senior counsel at the Becket legal group, told CNA Dec. 11.

Windham said the court ruled that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act “gives religious claimants another way to protect their rights.”

“Again and again, we have seen cases where a government official violates someone’s religious freedom rights, then backs down when he or she has to go to court,” she said. “That leaves the religious person without any way to protect her rights in the future.”

The Becket Fund, a legal group focused on religious freedom issues, had filed an amicus brief in the Supreme Court case Tanzin v. Tanvir.

The case ruled on a lawsuit brought by three Muslim men, Muhammad Tanvir, Jameel Algibhah, and Naveed Shinwari, who said they were placed on the FBI’s No-Fly list in order to pressure them to act as informants on Muslim communities. They sought damages against individual officers, saying the matter falls under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, which bars government from unlawfully burdening religious practice.

The Supreme Court sided with the plaintiffs 8-0. Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who is new to the court, did not participate because the cases were argued before she was confirmed.

The lawsuit dates to 2013. The Supreme Court did not rule on the facts of the case, but on whether the plaintiffs could seek monetary damages against officers.

“A damages remedy is not just ‘appropriate’ relief as viewed through the lens of suits against government employees,” said Justice Clarence Thomas in the court’s Dec. 10 opinion.

“It is also the only form of relief that can remedy some (religious freedom restoration act) violations,” he said. “For certain injuries, such as respondents’ wasted plane tickets, effective relief consists of damages, not an injunction.”

Thomas said that the agents may cite the doctrine of qualified immunity to argue they are shielded from lawsuits, as the constitutional rights allegedly violated were not clearly established at the time of their conduct. However, that was not before the court.

Congress could take other actions to shield government employees from liability, he said, “but there are no constitutional reasons why we must do so in its stead.”

The plaintiffs were all U.S. citizens or green card holders. Tanvir, the lead plaintiff, was a lawful permanent U.S. resident living in Queens. He was a long-haul truck driver who would often fly home after finishing a delivery route. In October 2010 he was turned away attempting to fly home from Atlanta. Two FBI agents took him to a bus station and his trip home took 24 hours.

Tanvir quit his job, but faced other problems trying to visit his ailing mother in Pakistan. He was not allowed to fly three separate times, after purchasing plane tickets. FBI agents allegedly told him he would be removed from the No Fly list if he became an informant.

The Trump administration has been generally supportive of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, but in this case for its dismissal. The lawsuit would interfere with “sensitive matters of national security and law enforcement,” lawyers for the government argued.

Becket argued that government bodies commonly change harmful actions or policies as soon as they are challenged in court, then argue that because the harm has stopped those affected cannot bring a lawsuit.

“This doesn’t happen in every case, but when government officials have egregiously and knowingly violated someone’s religious freedom rights, they can be held accountable for their actions,” Windham commented. “If the case had gone the other way, it would mean there was no way to vindicate egregious violations of rights, so long as the government official backed down before the court rules.”

Windham said it was important to note that the court didn’t say how much the damages should be or decide whether the agents broke the law.

“This case just allows plaintiffs to have their day in court, and try to prove their claims,” she told CNA. “We have seen government actors violate religious freedom, and then back down, in cases involving free exercise on college campuses, churches using their own land for religious exercise, and prison inmates who want to worship or study religious materials. This decision makes it harder for government officials to get away with repeated violations of religious freedom.”