Question of Faith: How did the Church respond to Past Pandemics?

The Church, like humankind in general, has faced challenges posed by disease. And where there has been suffering, Christians have responded, seeking to overcome fear and self-interest to offer spiritual, physical and material support.

COMMITMENT TO CHARITY

Based on Jesus’ words and example, the first Christians shared their resources to care for the least among them, including widows, orphans and the poor. But they reached beyond their members,

developing the most extensive network of charity that the world has ever known.

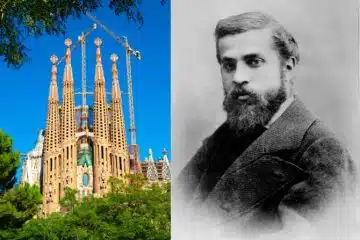

Concern for others’ needs grew to include care for their health. Sickness was not well understood and often considered a punishment for sin, but Christians destigmatized sickness as responsibility for the sick and it became recognized as a religious duty. By the Fourth Century, Christian bishops took the lead, founding hospitals and hospices. Basil of Caesarea built a charitable complex (including a hospital) that was so vast that it was nicknamed “the new city.” Some who assisted the bishops formed communities dedicated to charitable works, developing religious orders to nurse the sick, pray with them and assure those who died received a proper burial.

The Christian network of care became more critical during times of pervasive illness. The so-called Plague of Cyprian (named for the bishop who most fully described it and sought to aid its victims) ravished the Roman Empire in the mid-Third Century. While non-Christians fled from their sick friends and family, Christians remained to care for them. Impressed by their witness, many non-Christians who survived the outbreak converted.

SANCTITY OUT OF SUFFERING

At times, the magnitude of disease could be overwhelming. During the Black Death in the mid-1300s, at least one-third of Europe fell victim, including many priests and religious who cared for

the ill or provided them with the last sacraments. St. Roch, who is frequently invoked against illness, became sick after tending to plague victims. He recovered and continued his ministry. According to some accounts, after making the sign of the cross over them, many ill persons recovered. Though he did not die of the plague, he became the patron saint of plague sufferers; his saintly intercession was credited with turning back an epidemic in Germany in 1414.

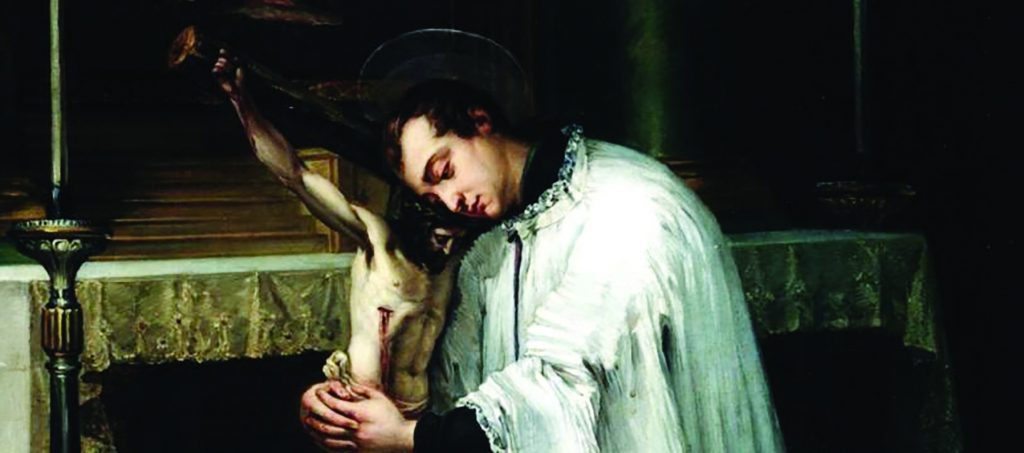

Outbreaks of disease frequently elicited Christian heroism. In the late 16th Century, St. Aloysius Gonzaga, a young Jesuit, visited the victims of the plague at a Roman hospital, continuing to go to the hospital even after his superiors, out of concern for his health, cautioned against it. He contracted the illness and died at age 23. The life of St. Aloysius, known today as the patron of students and caregivers, continues to inspire.

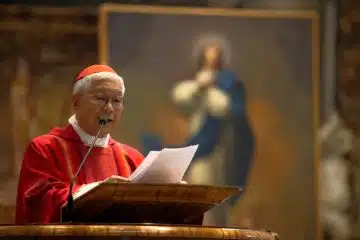

THE COMMON GOOD

As modern medicine advanced in the 19th Century, the Church continued to lead, extending healthcare to many underserved communities. Women’s religious communities established and staffed hospitals and clinics, and, during time of pandemic, thousands of additional sisters volunteered to aid the sick, forming a veritable army of caregivers.

With a greater understanding of how to slow the spread of disease, the Church has cooperated with governments that have emphasized canceling events, including religious services. During the

1918 influenza pandemic, numerous U.S. cities forbade large gatherings. Though Mass could not be celebrated publicly, Catholics were encouraged to amplify their prayers and devotions at home as the Church assisted in protecting those in society most vulnerable to illness.

The Church’s response to disease remains motivated by the same concerns: aiding the sick and suffering and serving the common good. Through spiritual assistance and physical care, we, as Catholics, seek to help those impacted by the most recent pandemic, continuing a long tradition dating back to Christianity’s earliest years.

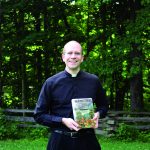

FATHER DAVID ENDRES is associate professor of Church history and historical theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology.

FATHER DAVID ENDRES is associate professor of Church history and historical theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology.