Our common humanity, our common call

June 5, 2012

By Father Benedict O’Cinnsealaigh

I was born and raised in Dublin, Ireland. The greatest diversity we had was among those born in North Dublin and those born and raised on the other side of the river Liffey, in South Dublin. My experience of diversity was limited to say the least.

Yet, even in Ireland, there were deep social, economic, regional, political and historical divisions. The divisions cause by colonialism and civil way were deep, painful and lasting.

When I arrived in the States 18 years ago, I found a new world in more ways than one. All aspects of life, accents, language, slang, landscapes, customs, diet, shopping, and culture had a tremendous diversity. I also found people of many different colors and different ethnic background integrated into the everyday life of the community. It was a fascinating discovery, but one with many challenges as well. I began to understand the proximity of diversity, but also the barriers that it could establish among people.

In some of the smaller cities of the archdiocese, I found two Catholic churches often close together. One was for the Germans, the other for the Irish (or any other local ethnic group) which, apparently in days gone by, weren’t able to worship together because of language, culture and customs. Most of these communities had long since melted into one but others remained in their place. So I had to ask myself, how did the blending happen? And, how could it happen still for communities of whites, African-Americans, Hispanics, Caribbean natives and all the other groups? What were the vehicles that carried people over boundaries and beyond cultural, racial and ethnic walls? Obviously, if there were a simple answer, we wouldn’t even be discussing it now.

One thing struck me as a possibility. I asked myself the question; what joined the separate groups together in my own homeland experience? The answer seemed to be a common cause, a common hope and vision. For us in Ireland, the glue that bound us together was a common religion and a sense of patriotism or dedication to our common story over the centuries. We admired the same heroes and heroines, the great saints, and were aware of the struggles that our people had endured against injustice, oppression and servitude. Underneath all the many differences lay the common human experience of faith, dreams and hardship.

On further thought, it occurred to me that this was not just the story of Ireland but, in reality, the story of all humanity. We can travel throughout the world and find the patterns repeating themselves in every place and in every culture. I know there is a tendency for everyone to think that their story is worse than anyone else’s but, in fact, the similarities are greater than the differences. It becomes then the human story, the story of everywhere and everyone. It might be here that we could find a way to join hands in the faith across cultures and divides.

Our common humanity makes us share the one deepest reality of the whole human race, that we were created by a loving God to know Him. to love Him, and to be with Him forever.

Perhaps this sounds naïve and unrealistic and so it would be if left in a dreamy idealistic world of ideas. But throughout the long story of humanity, it has happened in the realm of the real, the historical. I once recall an English woman who taught a course on English history saying, “There is no such thing as an Englishman.” Are we Celts, Saxons, Picts, Norsemen, or Bretons? We are all of them and now we include Africans, Islanders and sub-continent peoples. Her point was we are all human persons who, while being different in many ways, are one in our common location, common interests and our common hopes.

So I wondered, could the revelation of Jesus Christ mediated by the magisterial authority of the church provide the arena for a common vision of human life and human possibilities? Might the proclamation of the faith and the authentic living of it in fundamental charity and humility become for us a beginning of the resolution to the great problems of diversity as exists among us as a force of division rather than of unity? Just a question, maybe. But, could it be a place for us to explore?

All vocations are first a call from God but the same vocation is either nourished or starved within the family, community, and church, in which they are planted. Maybe, if we as Catholic families, the church community, or church communities, are willing to accept our common human heritage of struggle and victory, pain and hope, death and life, maybe then we would have a vision and value of life that is worth handing on to the next generation.

If we are willing to take the Gospel commandments seriously: love one another, and “what I have done for you I ask you to do for one another,” maybe, then we will have a vision of life that our young people feel has something to say to them, challenge them, and offers them a future that is richer than the past, a future worth building, and values worth embracing. Maybe, this is the environment that produces vocations: mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, religious and priests. If we choose to live this type of heroic love for each other, maybe then, our hope can become a reality.

Father O’Cinnsealaigh is the president/ rector of the Athenaeum of Ohio/Mount St. Mary’s Seminary.

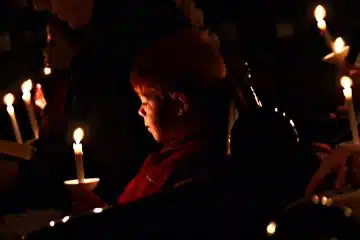

![The night is advanced, the day is at hand. Let us then throw off the works of darkness [and] put on the armor of light Romans 13:12 Rorate Mass Old St Mary (CT Photo/Greg Hartman)](https://www.thecatholictelegraph.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/DSC_0569a-360x240.jpg)