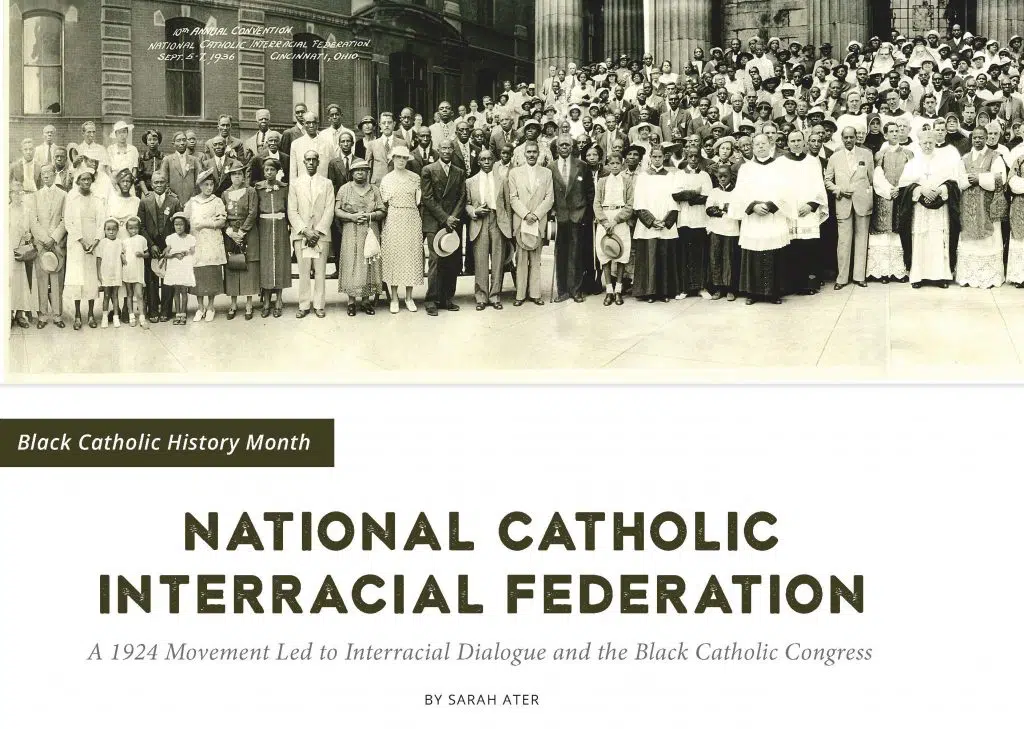

National Catholic Interracial Federation

Early 20th Century America saw a modern, concerted effort to promote the Black community’s rights, needs and dignity. However, movements were difficult to sustain. In Cincinnati during the 1880-1890s, Daniel Rudd published the short- lived, groundbreaking newspaper American Catholic Tribune to evangelize the Black community, and founded the Black Catholic Congress, which met annually for its first years of activity, then became inactive for several decades.

Early 20th Century America saw a modern, concerted effort to promote the Black community’s rights, needs and dignity. However, movements were difficult to sustain. In Cincinnati during the 1880-1890s, Daniel Rudd published the short- lived, groundbreaking newspaper American Catholic Tribune to evangelize the Black community, and founded the Black Catholic Congress, which met annually for its first years of activity, then became inactive for several decades.

In Maryland during 1924, Dr. Thomas W. Turner, son of former slaves and an accomplished educator, botanist and activist, founded and led as its first president the Federated Colored Catholics, a Black-only organization designed to unite the roughly 250,000 Black Catholics in America. The Federation’s constitution outlined its goals to advance the spiritual and temporal needs of Black Americans; education, housing, status in the Church, and work opportunities were critical. They decried the lack of Black priests and pressed for their admittance in seminaries. Local chapters formed to advocate the Federation’s causes with their local bishops and parishes.

They held annual meetings at different locations, and met twice in Cincinnati. The first, in 1928, was a one-day conference on “The Negro in Industry” and included Archbishop John McNicholas, O.P. and Dr. Turner as speakers.

Professor Victor Daniel, principal of the Cardinal Gibbons Institute, a Catholic High School for Black students, spoke pointedly about the racism problem and Black workers being denied positions and proper training. These restrictions stressed an idea that Black men were inferior, an attitude difficult to reconcile with Christian teachings of the “Fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man,” a phrase used regularly by Daniel Rudd.

Dr. Turner commented on the need to form a Catholic Interracial Committee for making progress together and giving greater glory to God. His interracial committee idea grew beyond Dr. Turner’s vision, and it was soon proposed that the Federation itself become interracial. At its September 1932 meeting, the name changed to the “National Catholic Federation for Promotion of Better Race Relations,” then an “illegal” meeting held in December voted Dr. Turner out. This movement was led by two white Jesuit priests, John LaFarge Jr. and William Markoe, who wanted the Federation to be unitive of the races rather than form separate groups. Cincinnati Black attorney George W.B. Conrad was elected president.

By their 1936 meeting in Cincinnati, the group’s name changed again to the “National Catholic Interracial Federation.”

Archbishop McNicholas spoke at length during this meeting regarding the Black community’s housing situation. “We have in Cincinnati a so-called slum-clearing project. The interests of the Negro were disregarded. Many Negroes have had to withdraw from the area that has been cleared in order to make way for the new buildings. They are going to suffer the most, because rents in the new developments will be too high for them.” He also spoke to the need for Black churches, schools and priests to serve the people.

Resolutions adopted include praying for Blessed Martin de Porres’ canonization, decrying injustices against Black people, especially lynching, urging the greater need of Catholic Church facilities to provide education among the Black apostolate, and deploring the trouble in Spain, including a declaration against communism and fascism. Moves were also made for the Federation’s cooperation with committees at the National Catholic Welfare Conference and Councils of Men and Women.

Annual meetings continued until the early 1950s, when the organization disbanded. However, the Federation’s goals remained in the hearts of many and led to the Black Catholic Congress’ resurgence in 1987.

Resolutions adopted included praying for Blessed Martin de Porres’ canonization, decrying injustices against Black people, especially lynching, urging the greater need of Catholic Church facilities to provide education among the Black apostolate…

This article appeared in the November edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.