Missionary sister brings Christ’s love to Brazilian interior

Since 1970, Sister of Notre Dame de Namur Rebeca Spires has made the interior her mission.

For more than four and a half decades, Sister Rebeca has brought Christ’s love to poor farm workers and the indigenous people of the Brazilian interior.

“Jesus touches every person He cures,” Sister Rebeca said. “He goes way beyond curing. He enters their lives. He gets up close and personal. It’s a throng, not a few folks, but He gives every one of them special attention.

“This touching, this personal tenderness of Jesus is repeated often in the Gospels. This is the model for my mission. Among the Indians — peoples who have been historically denied their rights, decimated, destroyed — one sees multiple manifestations of kindness, tenderness that only can come from God,” said Sister Rebeca, who was born and raised in Columbus, and entered the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur in 1958.

“I my preparation for this ministry I was told: ‘Remember, the first missionary to walk there was Jesus.’ No matter that the people do not know His name, they know His goodness. They are so close to nature they absorb the divine. Now modern times are altering the indigenous way of life but normally there is no such thing as abandonment in the (Brazilian) village. The world abandons the Indians, but they take care of each other. Those with physical handicaps, the elderly, the mentally ill, all are cared for with loving tenderness and not only by their own family but by the community.

“Our Indian Mission Council (Sector of the Bishops’ Conference for the Indigenous Peoples) is a sign that God loves, doesn’t forget, and walks with them. Brazilians in general, including Indian peoples do not give up hope. They always believe tomorrow will be better.”

Sister Rebeca graduated the former Our Lady of Cincinnati College where she received a bachelor of science degree in education. She spent seven years teaching with postings in Columbus, Arizona and Dayton, but the missions were a constant call.

Her first years of what would become a continuing 28-year vocation was with Brazilian farm workers.

“I lived in Maranhão with four sisters and (Sister) Dorothy Stang was my mentor,” she said. Sister Dorothy was murdered in Anapu, a city in the state of Para in the Amazon Basin where Sister Rebeca ministers today. Sister Dorothy had been outspoken in her efforts on behalf of the poor and the environment, and had previously received death threats from loggers and landowners. Her cause for canonization as a martyr and model of sanctity is underway within the Congregation for the Causes of Saints.

“Our main activity was in the interior with poor farmers with whom we shared the faith and the firm conviction that God’s children must be respected in their God-given rights to till the land and provide for their families,” Sister Rebeca said.

At the time, Brazil was under a military dictatorship supporting wealthy landowners who exploited the poor. “When the people formed a Farm Workers Union … (and) because of the difficulties working land in Maranhão, many were migrating to Para,” she said. The Sisters followed and in 1974 opened a new Notre Dame Mission in the diocese of Marabá, Pará. A revolutionary movement was afoot in the forested area attempting to destitute the dictatorship. “The Catholic Church stood by the people, but it was not easy. Several of our Brazilian colleagues were arrested and tortured by the military. All were questioned. ”

In 1976, Sister Rebeca was invited to participate in a missionary group directed to the indigenous peoples. “There was a whole period of preparation and tentative visits to the villages close by before actually moving to a Karipuna village to live in 1978.

“The Karipuna were Catholics, holding onto their religion with litanies in Latin and the Catechism their ancestors had learned and passed on in song. Like the relationships among themselves their relation to God was based on reciprocity: I give you something; you give me something. So they made promises to God or to the saints to do something special if their prayer was answered — almost always a cure for illness. Meanwhile they continued their original practices of shamanism in a mixture that worked for them.

“I was called to help with schooling… They spoke only their language — a patois of French, Bantu, Nheengatu and Karib…. They taught me to speak their language and help plant fields while I helped them create a written alphabet — until then it was an oral language. From that humble start, today there are more than 150 Indian teachers in 53 villages of the Karipuna, Galibi-Marworno, Palakir and Galibi‐Kalinã Indians.

“We studied the Bible and wrote songs for the Sunday celebrations in their language and we tried new ways of celebrating the liturgy,” Sister Rebeca explained.

A transformation is evident today.

“There are the simple things like filters for drinking water and outhouses which have diminished dysentery to almost extinction and vaccination campaigns which have eradicated yellow fever and diminished other fatal illnesses. The forming of associations where different ethnic groups who share the same territory come to agreement about regulating fishing and hunting to guarantee a continuity of the food source. Reconciliation services are held annually – with or without the sacrament in which people ask pardon personally of one another and/or publically of the whole community.

“There are dynamics for restoring harmony, including in nature. When one is about to cut down a tree to make a canoe or build a house or a bridge, first one talks to the tree and explains the necessity. When one kills an animal to eat, her performs a ritual to bring harmony back into the world. And so it goes among the Indians. Reconciliation is part of daily life. When someone transgresses a norm — physical aggression, lying, stealing — the chief and the council give punishment which consists of service to community.”

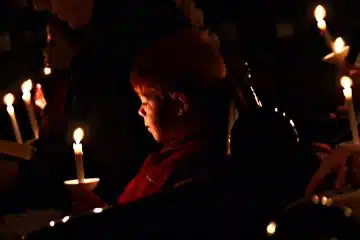

Through it all Mary is beloved in Brazil.

She has multiple names and titles and is treated with majesty, tenderness, intimacy,” Sister Rebeca said. “It is because of her that no one ever doubts forgiveness, whatever the wrong doing, because of the certainty she will intervene and Jesus can refuse her nothing. She is quoted, revered and totally loved. Above all she is Mother. Earth is Mother. A mother will always love her child no matter how awful he may be. This is the Brazilian perception, especially among the simple folks who know the heart of God directly.”