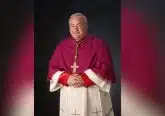

Meeting pope, Irish prelates discuss ministry of bishop, abuse scandal

IMAGE: CNS/L’Osservatore Romano

By Cindy Wooden

VATICAN CITY (CNS) — Telling the bishops of Ireland that he wanted to hear their questions, concerns and even criticisms, Pope Francis spent almost two hours in conversation with them.

In the continuing evolution of the “ad limina” visits bishops are required to make to the Vatican, Pope Francis met Jan. 20 with 26 Irish bishops and set aside a practice that began with Pope Benedict XVI: writing a speech to the group, but handing the text to them instead of reading it.

Pope Francis did, however, maintain his practice of sitting with the bishops and asking them what was on their minds.

The ministry of a bishop, the clerical sexual abuse crisis, the role of women in the church, the need to find new ways to engage with young people, the changing status of the church in Irish society, the importance of Catholic schools and methods for handing on the faith were among the topics discussed, the bishops said. They also spoke about plans for the World Meeting of Families in Dublin in August 2018 and hopes that Pope Francis would attend.

Archbishop Eamon Martin of Armagh, Northern Ireland, president of the bishops’ conference, told reporters that Pope Francis led a serious reflection on “the importance of a ministry of presence, a ministry of the ear where we are listening to the joys and the hopes, the struggles and the fears of our people, that we are walking with them, that we are reaching out to them where they are at.”

“The meeting this morning was quite extraordinary,” said Archbishop Diarmuid Martin of Dublin, one of the few Irish bishops who had made an “ad limina” visit previously; the previous time the Irish bishops made one of the visits to report on the status of their dioceses was in 2006.

“The dominant thing was he was asking us and challenging us: What does it mean to be a bishop?” the Dublin archbishop said. “He described a bishop as like a goalkeeper, and the shots keep coming from everywhere, and you stand there ready to take them from wherever they come.”

The Armagh archbishop said meeting with different heads of Roman Curia offices and with the pope, “we haven’t received any raps on the knuckles,” but rather felt a desire to hear the bishops’ experience and their ideas for dealing with a situation in which the voice and authority of the church in the lives of individuals and society has diminished rapidly.

“We are realistic about the challenges we are facing in Ireland at the moment,” he said. “But we are also hopeful that we are moving into a new place of encounter and of dialogue in Irish society where the church has an important voice — not the dominating voice or domineering voice that perhaps some say we’ve had in the past — but we are contributing to important conversations on life, on marriage, on the family, on poverty, homelessness, education.”

One of the factors pushing such a rapid loss of public status for the church in Ireland was the sexual abuse scandal, he said. And as he told Pope Francis, just as the bishops were meeting with the pope, in Belfast leaders of the Historical Institutional Abuse Inquiry in Northern Ireland were making public their report on the abuse of children in residential institutions, including some run by Catholic religious orders.

One of the first meetings the bishops had in Rome, he said, was with staff of the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, sharing the steps the Catholic Church in Ireland has taken to prevent further abuse, to bring abusers to justice and to assist survivors “affected by the awful trauma of the sins and crimes of people in the church.”

Archbishop Martin told reporters there was a recognition that Ireland had gone “through a bad time — not for us, but particularly for children who were abused, and that anything that we did would inevitably be inadequate in responding to the suffering they experienced.”

He also told reporters the bishops brought up the role and position of women in the church during almost every meeting they had, including at the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, where they discussed “the areas within the church where a stronger position of laypeople is not only licit, but is desirable.”

“One of the groups that is most alienated in the Catholic Church in Ireland is women, particularly young women, who feel excluded and therefore do not take part in the life of the church,” he said.

The bishops, he said, found “a willingness to listen and an awareness that we were asking a valid question rather than something we should not be talking about.”

After about 90 minutes of conversation with Pope Francis, the Dublin prelate said, the pope asked if the bishops were tired. In the past, he said, that was signal that the pope was tired and the meeting was about to end. Instead, the conversation continued for another 25 minutes.

– – –

Follow Wooden on Twitter: @Cindy_Wooden.

– – –

Copyright © 2017 Catholic News Service/U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. www.catholicnews.com. All rights reserved. Republishing or redistributing of CNS content, including by framing or similar means without prior permission, is prohibited. You may link to stories on our public site. This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To request permission for republishing or redistributing of CNS content, please contact permissions at [email protected].