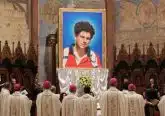

Kansas priest recalls friendship with martyr as beatification nears

IMAGE: CNS photo/Karen Bonar, The Register

By Karen Bonar

CAWKER CITY, Kan. (CNS) — In the cozy rectory behind Sts. Peter and Paul Church sits Father Don McCarthy with myriad items relating to his friend, Father Stanley Rother.

“It’s kind of like a shrine in here,” he said, looking around.

At the window was a framed picture of Father Rother with Guatemalan children. Father McCarthy has a box dedicated entirely to correspondence from his seminary chum. “He and I were close friends,” the retired priest told The Register, newspaper of the Salina Diocese.

He will be among the throngs gathering Sept. 23 at the Cox Convention Center in Oklahoma City to witness the beatification of Father Rother, a priest of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City.

Father Rother was gunned down in the rectory of his church in Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala. He was considered a martyr by the church in Guatemala. Pope Francis formally recognized the missionary priest as a martyr Dec. 2, clearing the way for his beatification.

Originally from Galveston, Texas, Father McCarthy attended the seminary in San Antonio during the 1950s.

“Stan and I?were not in the same class in the seminary, but we got to be good friends, due to working together in the book bindery and visitations at each other’s homes in vacation time,” Father McCarthy said.

Father Rother was two years behind Father McCarthy. Eventually, the Oklahoman was asked to leave because he struggled with Latin.

“All of the philosophy and theology textbooks and canon law were all in Latin. That’s the way things were then,” Father McCarthy said.

Yet Father Rother didn’t give up on his vocation. Bishop Victor J. Reed, who headed what was then the Diocese of Oklahoma City-Tulsa from 1958 to 1971, helped the young student enroll at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland.

“We kept in touch,” Father McCarthy said. “I used to visit in the summertime. I would stay at Stanley’s home and tried to help at farm work, but I wasn’t very good at it. When I was ordained in 1959, he and his mother came to Galveston for my first Mass. He was thurifer (altar server who carries the censer) for my first Mass.”

In return, Father McCarthy participated in Father Rother’s first Mass in 1963.

In 1968, Father Rother went to Santiago Atitlan on assignment from Diocese of Oklahoma City-Tulsa. (In 1972, Oklahoma City was elevated to an archdiocese and Tulsa was established as its own diocese.) Called “Padre Francisco” and “Padre Aplas,” he helped the locals build a small hospital, school and radio station. He also taught the locals improved methods of farming and fishing.

Despite his early difficulties with Latin, Father Rother translated the Mass and several parts of the New Testament into Tzutujil, the language of his parishioners, Father McCarthy said.

“He and I stayed in contact when he went down to Guatemala,” Father McCarthy said. “He was very much a part of the community for years.”

The mission was about 10 years old when Father Rother arrived, with a staff of 10. “But gradually over the years, he was the only one left,” Father McCarthy said.

The Rother family and his friends knew the continued presence in Guatemala was dangerous. The country was in the midst of a brutal civil war, lasting from 1960 to 1996.

“He knew he was on a death list,” Father McCarthy said. “(His family) encouraged him to stay (home), but he went back. He always said, ‘The shepherd cannot run.’ I was always edified by his attitude. He could have stayed home and been safe, but he said, ‘I want to be with my people.'”

Father McCarthy remembered getting the call informing him of his friend’s death July 28, 1981. He was touched that the Rother family thought to call him a mere 24 hours after the murder.

“After Stanley was killed, they kept his heart in a shrine in his mission church,” Father McCarthy said. “It’s still there as a shrine.”

The Guatemalan church wished to keep Father Rother’s body, but it was returned to Oklahoma and he was buried in Okarche in 1981.

“I was not surprised to hear that he was up for sainthood,” Father McCarthy said. “The Guatemalan people considered him a martyr right away. Being a martyr was one way to become a saint. Once you’re declared a martyr, it cleared the way for his beatification, which is the next to last step to sainthood.”

Because of their friendship, Father McCarthy was one of many people called to give testimony about Father Rother’s life and ministry as part of his sainthood cause. In general, following beatification, a miracle attributed to the intercession of the sainthood candidate is required for that person to be canonized.

He said his friend’s life serves as an example for everyone.

“All of us are called to make sacrifices in life,” Father McCarthy said. “Maybe not the supreme sacrifices (Father Rother) did, but all of us need to realize we have duties and obligations we cannot run from.”

– – –

Bonar is editor of The Register, newspaper of the Diocese of Salina.

– – –

Copyright © 2017 Catholic News Service/U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. www.catholicnews.com. All rights reserved. Republishing or redistributing of CNS content, including by framing or similar means without prior permission, is prohibited. You may link to stories on our public site. This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To request permission for republishing or redistributing of CNS content, please contact permissions at [email protected].