Father Hesburgh: A transformative figure in U.S. higher education

By Chaz Muth Catholic News Service

WASHINGTON — When the University of Notre Dame invited President Barack Obama to be its 2009 commencement speaker, it unleashed a firestorm of criticism on one of the country’s most recognized U.S. Catholic institutions of higher education.

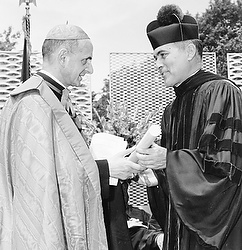

Holy Cross Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, who retired as president of the university 22 years earlier, staunchly defended the school leadership’s decision to invite the first black U.S. president to speak at the university and receive an honorary degree.

But Obama’s support for abortion rights and embryonic stem-cell research, both strongly opposed by the Catholic Church, led about 80 U.S. bishops as well as university donors, alumni and others to decry the invitation.

And it reignited a heated debate about maintaining the Catholic identity of U.S. Catholic colleges and universities.

Father Hesburgh, who died Feb. 26 at age 97, came in for his share of criticism, too, for supporting the school’s choice of Obama. He firmly stated that no speaker who had ever come to Notre Dame had changed the Indiana university, but that often a speaker had been changed by his or her experience on campus.

Father Ted — as the longest-serving president of Notre Dame was affectionately known — will be remembered by many as a transformative figure in higher education in the nation.

One of the most influential marks he left on Catholic higher education happened in 1967 when he assembled several of the country’s leading university presidents at the Congregation of Holy Cross retreat center at Land O’Lakes, Wisconsin.

The gathering produced a document titled “Statement on the Nature of the Contemporary Catholic University,” better known as the Land O’Lakes statement, said R. Scott Appleby, dean of the Donald R. Keough School of Global Affairs at Notre Dame.

It emphasized that Catholic universities must have autonomy and academic freedom in the face of the authority of lay or clerical entities external to the academic community itself.

The document was controversial in its time, and even today Catholic educators who believe it contributed to the secularization of many U.S. Catholic universities still criticize it.

Father Hesburgh’s bold leadership in the face of reproach was not uncommon and it’s what helped distinguish him as having had an extraordinary impact on higher education in the U.S., “and by no means just Catholic higher education,” said William G. Bowen, retired president of Princeton University.

“As always, Ted said what needed to be said, courageously and clearly,” Bowen said when discussing the priest defending Notre Dame’s decision to invite Obama. “It’s a striking example of Father Ted’s passionate defense of both the teachings of his own faith and the importance of recognizing, learning from and, yes, honoring those with different views.”

Academic leaders past and present traveled to Notre Dame March 3-4 to pay homage to the priest credited with transforming the small Catholic college of the 1950s known for its football team into what is often called the world’s pre-eminent Catholic university.

Many were quick to point to his leadership as chair of the International Federation of Catholic Universities and his vocal opposition to sending federal troops onto college campuses during the social upheavals of the 1960s.

In 2000, Father Hesburgh was the first figure in higher education to be presented with the Congressional Gold Medal for his public service as president of Notre Dame, his work on behalf of civil rights and efforts for international peace.

Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice told more than 10,000 people at a March 4 memorial tribute on the Notre Dame campus that as a student there she was honored to attend a university where the president was recognized internationally.

However, it was the personal attention he gave to students that most endeared him to her.

“You could walk along the quad, you could see Father Ted talking to students about the issues of the day, equality and peace and justice,” Rice said. “He had us engage in a day of fasting to remember what it was like to be hungry. And, when a light was on in the president’s office just beneath (Notre Dame’s iconic) golden dome, students would point and say, ‘Father Ted is working late tonight.’

“Somehow his touch was so personal that even those who met him once, or maybe never at all, knew him, and they loved him, just as he loved Notre Dame.”

The emcee of the memorial tribute, NBC News correspondent Anne Thompson, told the audience that when she was a student at Notre Dame in the late 1970s, there was a common joke told on campus: “What’s the difference between God and Father Hesburgh? The answer, God is everywhere. Father Hesburgh is everywhere but Notre Dame,” a reference to his world travels as an adviser to popes and U.S. presidents.

“Back then we were very jealous children,” Thompson said, “as Father Ted used our university here in South Bend as his launching point to change the world.

“Believe me, we were all so very proud that popes and presidents consulted with Father Ted,” she said. “But, we wanted his undivided attention and we wanted it 100 percent of the time. But, as always, Father Ted knew best.”

Some complained his frequent travels to serve on presidential commissions and to help establish the Tantur Ecumenical Institute in Jerusalem at the request of Blessed Paul VI took him away often during his 35-year tenure as president of Notre Dame, but others argued such endeavors helped to establish the school as a world-class university.

“He quite literally put Notre Dame on the map,” said Jesuit Father William J. Byron, who was president of The Catholic University of America in Washington from 1982 to 1992.

Under Father Hesburgh’s presidency — from 1952 to 1987 — Notre Dame’s annual operating budget went from $9.7 million to $176.6 million; the endowment rose from $9 million to $350 million; research funding climbed from $735,000 to $15 million; enrollment more than doubled; women were admitted; and the governance transferred from the Congregation of Holy Cross to a mixed board of lay and religious trustees and fellows.

“Notre Dame is a far better institution today as a result” of lay-religious control, Father Byron said. “He led the effort to give theology primacy of place and establish the compatibility of faith and reason in a university setting and was a strong defender of academic freedom in the American tradition.”

“Father Ted’s abiding concern was with Notre Dame’s fidelity to its Catholic mission,” said Holy Cross Father John I. Jenkins, the current president of Notre Dame. “He was always convinced that Notre Dame could not serve the church in the world effectively unless it sought genuine scholarly excellence and this could not be achieved without enjoying appropriate institutional autonomy and academic freedom.”

“His overall impact on American higher education was enormously positive,” Father Byron said. “He demonstrated how a university president could be a servant leader.”

Posted March 13, 2015