Death and Dying with Dignity

Twenty years ago, during the AIDS crisis, many Africans said, “You’re either infected or affected.” In this time of pandemic, many could say the same. If we haven’t personally suffered the loss of a loved one, we know someone who has.

Everyone has seen the death tolls of those who have succumbed to COVID-19, as well as the thousands hospitalized. At home and abroad, millions have suffered and died alone, some without and the sacraments. The fear of such illness has, as its natural end, a fear of death.

WILL I HAVE ANY DIGNITY WHEN I DIE?

The Easter season provides a hopeful moment to reframe death within the glorious light of the Risen Lord, who says, “Behold, I make all things new.” (Rev. 21: 5). Human beings derive their value from the fact that they are created in God’s image (Gen. 1:26); furthermore, Christ’s Incarnation sanctified the human person in a special way, imprinting upon us a dignity that is as immutable as Jesus Christ Himself (CCC 357).

Death has no power over our dignity, or effect on our value in the eyes of the Creator. Proponents of assisted suicide and euthanasia use the phrase “death with dignity” to describe their solution to suffering an unbearable illness: medical homicide. They suggest surrendering to the fear of a prolonged death to preserve dignity. However, to Christians, death is an element of the world, imbued with the “grandeur of God,” Who will not permit the dignity of a single soul to diminish.

Prominent Catholic scholars and physicians, such as Daniel P. Sulmasy, have distinguished between “inherent” and “attributed” dignity. Inherent dignity is unchangeable, inviolable, and reflects the nature of our Creator. No illness or suffering, however terrible, can revoke it.

In contrast, attributed dignity is that imperfect and changeable value we ascribe to individuals. This perception of dignity can diminish as we experience the frailty, physical sickness and loss of control that accompanies serious illness and death. The loss of attributed dignity is better described as being “undignified,” but it is not the same as inherent dignity.

To understand humanity’s encounter with death and its implications for dignity, we reflect on the death of Christ. Isaiah reminds us that Jesus’ death was hardly a dignified one: “Yet it was our pain that he bore, our sufferings he endured. We thought of him as stricken, struck down by God and afflicted. But he was pierced for our sins, crushed for our iniquity. He bore the punishment that makes us whole, by his wounds we were healed” (Is. 53:4-5). Despite His gruesome, terrifying death, Jesus retained His dignity to the end and elevated it as a part of human existence before He ultimately overcame its power.

Will we have dignity when we die? The answer is yes. Dignity transcends our perception and senses. We recognize our inherent dignity, derived from Christ the Suffering Servant, throughout our lives and even unto death. As St. Thérèse of Lisieux wrote, “It is not Death that will come to fetch me, it is the good God. Death is no phantom, no horrible specter, as presented in pictures. In the catechism, it is stated that death is the separation of soul and body: that is all! Well, I am not afraid of a separation which will unite me to the good God forever.”

WILL I DIE ALONE?

With Christ, we can never truly be alone, even if we are physically alone, or feel lonely. Where does that place us when our loved ones, our patients, our neighbors or strangers face death? Precisely where Mary and St. John found themselves

– at the foot of the Cross. In those dark three hours, they, like Christ, demonstrated the ideal human response to death. Silent, steadfast and prayerful, they recognized what Pope St. John Paul II described as both “a call and a demand.” When a suffering person is dying, we should heed his or her “call” to recognize in them the suffering and dying of Christ.

Pope St. John Paul II wrote in The Gospel of Life (51): “From the Cross, the source of life, the ‘people of life’ is born and increases.” The call of a dying person demands solidarity through our presence.

A recent Church document, entitled Bonus Samaritanus, stated: “To those who care for the sick, the scene of the Cross provides a way of understanding that even when it seems that there is nothing more to do, there remains much to do, because ‘remaining’ by the side of the sick is a sign of love and of the hope that it contains. The proclamation of life after death is not an illusion nor merely a consolation, but a certainty lodged at the center of love that death cannot devour.”

But when this is not possible, as during the pandemic or in the deaths of millions of others that die without family – in alleyways or under bridges, in our city streets or even in the wombs of distraught mothers – these deaths still have dignity. These beautiful people, created by God, are never truly alone or abandoned.

Even in death, Jesus echoed this promise to the “Good Thief” in their final moments: “Today, you will be with me in paradise,” (Lk 23:42-43). We should fear neither the loss of dignity nor dying alone. We can never die alone because we were never created to be alone.

Death is not to be feared; rather, it is a mystery to experience that can also be a gift – an opportunity for the dying person to sanctified and encounter the Mystery of God. For we who accompany the dying – even through prayer when we cannot be physically present – death is our chance to recognize the dignity in others that comes from Christ, a beautiful window to heed the “call and demand” of the dying.

Dr. Ashley K. Fernandes is a pediatrician who also holds a doctorate in philosophy from Georgetown University and is the associate director for the Center for Bioethics and an Associate of Pediatrics at The Ohio State University College of Medicine/Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

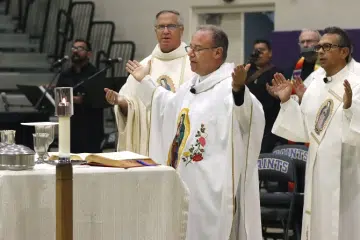

Father Earl K. Fernandes is the pastor of St. Ignatius of Loyola Church in Cincinnati and holds a doctorate in moral theology from the Alphonsian Academy in Rome.

This article originally appeared in the April 2021 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.