Daniel Rudd: “The Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of Man”

by Sarah Ater

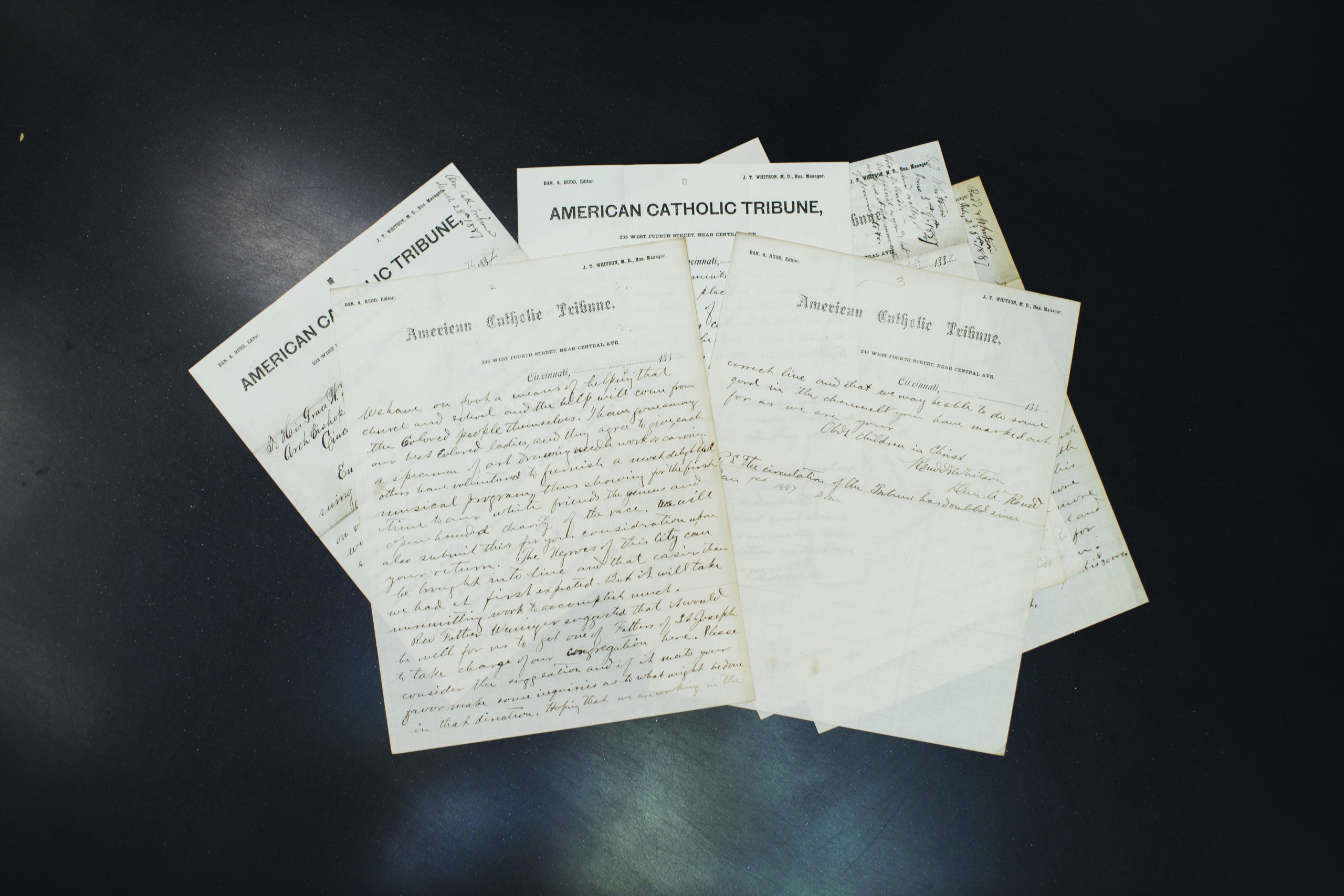

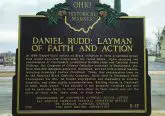

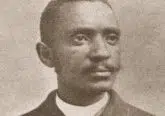

Daniel Rudd can be counted as one of the most influential Catholics during his time in the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. Indeed, his influence reached throughout the U.S. A man of deep faith, zeal for justice and untiring activity, Rudd founded the American Catholic Tribune (ACT), the first Black Catholic newspaper, and the National Black Catholic Congress. His Catholic faith influenced his world view – he saw the Church as the vessel of truth, justice and equality of all people before God.

He wrote, the Catholic Church was “the only place on the continent, where rich and poor, white and black, must drop prejudice at the threshold and go hand in hand to the altar” (ACT, Aug. 9, 1890, 2).

Born into slavery in Bardstown, KY, in 1854 to Robert and Elizabeth Rudd, Daniel and his family were devout Catholics and served as sextons at St. Joseph Proto-Cathedral. He would later reminisce about receiving instruction from the parish priest. As a young man, Rudd moved to Springfield, OH, to live with his brother, Charles. There he completed high school and attended St. Raphael Church. While there, he began his work in newspapers and established the forerunner of the ACT, the Ohio State Tribune. During this time, he was active in promoting racial equality, advocating for racial integration in the Springfield schools.

Rudd began publishing ACT in Cincinnati in 1886. His main audience for the newspaper was Black Americans, but Rudd knew that a large number of subscribers were white. He used the newspaper to share the Catholic faith, asking his readers to give the teachings of the Church a fair hearing. By observing history, they could see the teachings of the Catholic Church supported and uplifted the lowly, the poor and those cast down by society.

In ACT, Rudd also advocated for the recognition of the equality and the dignity of Black Americans; that no race is better than another, and that all are brothers and sisters before Jesus. Rudd was a hopeful and optimistic man, but he acknowledged how the stain of racism seeped into the Church, and he considered those Catholics who would separate people based on skin color as “less than Catholic.” In the pages of ACT, Rudd promoted the rights of African Americans on a practical level. He advocated for desegregation and he wrote passionately for higher education opportunities and vocational schools. ACT published through 1897.

When Rudd founded the Black Catholic Congress, his goal was to mobilize the laity into action. He was convinced there were more Black Catholics than what was known, if only an organization would rise up to give them a voice. The organization met five times between 1889-1894, the second held at the Cathedral in Cincinnati. However, because of the resistance met from some in the Church when talking about racism explicitly, the Congresses had to proceed gently, as amalgamation was still opposed in the Church. The Congresses focused on labor and trade unions to admit African Americans; the ongoing African slave trade and the support of “colored [religious] sisters.”

We remember Daniel Rudd for his deep faith and commitment to truth. He encountered many obstacles in his work, the persistent racism of people from within the Church, and saw the growing reality of Jim Crow laws. But he also saw the good in his fellow man and the potential for what humanity could be. His hope remained because he did not leave it with man, but placed it all in Jesus Christ.

Further reading: Gary Agee, A Cry for Justice: Daniel Rudd and his Life in Black Catholicism, Journalism and Activism, 1854-1933, 2011.

This article appeared in the November issue of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.