Coldwater Catholic faces Tourette’s syndrome with faith

September 4, 2012

By Bruce Holtgren

COLDWATER — Frank Bonifas has been cursed, yet blessed, with one of the most profoundly severe cases of Tourette’s syndrome ever recorded.

The neurological disorder itself has wracked his body with involuntary physical tics so awful that they have thrown out his back, given him indescribable neck pain and left him with migraine headaches that go on for weeks.

The neurological disorder itself has wracked his body with involuntary physical tics so awful that they have thrown out his back, given him indescribable neck pain and left him with migraine headaches that go on for weeks.

The extreme Tourette’s that Bonifas was born with also causes him to blurt — no, yell — the most vile, obscene, lurid, profane words and phrases imaginable. And at all the worst places and times one can think: in front of small children, in movie theaters, in schools.

And in Mass, too.

Could it get any worse? Yes — much. It all manifested itself when Bonifas was an adolescent: ages 13 to 19. And the majority of the small town he was been born in — Coldwater, Ohio, now a more tolerant burg of about 4,500 — just did not understand at all. For all world, he appeared to be possessed by the devil himself. Bonifas was mocked, teased, ridiculed. He was regularly beaten up at school, publicly shamed by his teachers, depantsed by bullies. Many folks assumed he said all these awful things on purpose, that he could stop those things if he would just try harder. (A handful of people still think so.)

Could it get worse yet? Oh, yes. In the 1960s and 70s, not even the experts knew what this bizarre disorder could be. His desperate parents took him to doctors in Lima, Dayton, even Columbus. A procedure, now presumed to be a lobotomy, was recommended. And, for an agonizing year and a half, he was confined in the psychiatric ward of University Hospital in Columbus, trapped with incompetent staff, dangerous patients and frightening conditions. His parents were told he should be locked away for the rest of his life.

Blessedly, he instead soon became among the world’s first “guinea pigs” to be treated for Tourette’s. In 1973, he was admitted to New York Hospital and was among one of the first three dozen people in modern times to be diagnosed with the disorder. Unbeknownst to anyone among his fellow small-town Ohioans, the medical pioneer returned to Coldwater with experimental drugs in his veins, a new man. Though far from cured, he was able to function, and eventually to interact with people. He graduated from high school, his circle of friends widened and his world opened up.

(There is still no cure for Tourette’s, now understood to be a spectrum disorder afflicting at least hundreds of thousands, from those with little more than rolling of the eyes or coughing, to people such as Bonifas who have multiple, extreme tics.)

Bonifas, 58, would be nowhere today without all that the body and the blood and the Spirit that his Catholic faith have nourished him with.

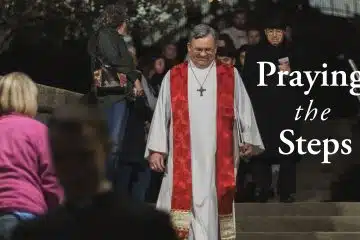

Father Thomas E. Dorn, who leads the Fort Recovery Cluster of parishes, has known Bonifas for many years, since Father Dorn was parochial vicar at Holy Trinity Parish in Coldwater.

“Frank has probably suffered more than any person I have ever met,” Father Dorn said in an e-mail, “yet he has persevered in life and in faith, through sufferings that would have long ago broken the spirit of many of us.”

Hearing Frank’s story today — he has written an autobiography, FU-FU-FU-FRANK! One Man’s Struggle with Tourette’s Syndrome — people often ask why in the world he simply didn’t commit suicide during those worst, most agonizing years of his young life.

His answer is one of the triumphs of faith: His Catholic upbringing taught him that suicide is a mortal sin. He knew that killing himself would result in eternal damnation for his soul, a torture infinitely worse than anything he would ever suffer on Earth.

Of course, Bonifas doesn’t mean all the awful words he still blurts out, nor the ridiculous habits such as poking or pinching the people he talks to, nor repeating words or sounds he hears. It’s Tourette’s. Bonifas calls you “Sweetheart.” He sends out 150 Christmas cards a year, each handwritten in beautiful Palmer penmanship. He asks if you’ve read his book. He reminds the town’s kids to not bully. He lives with and cares for his 87-year-old father, a World War II veteran who meticulously cares for an enormous vegetable garden. He mostly runs the household, yelling freqently, both because of his Tourette’s and because his dad is hard of hearing.

Everyone in Coldwater knows Frank and Jim Bonifas, of course. Frank’s mother, Rita, passed away in 2004 after years of her own suffering with Alzheimer’s. Jim visits her grave faithfully every day, tending it just as lovingly as the garden at home.

Coldwater is in Mercer County, 11 miles south of Celina, in Northwest Ohio, at the northern end of the Cincinnati archdiocese. Most everyone is Roman Catholic, “until we let the Methodists in,” as Bonifas jokes. The community, established by German Catholics, has rallied for years around Bonifas, who is now blessed by countless hundreds of friends. Many have been his friends for far longer than he has realized, truth be known; some protected him from bullies in high school, he’s quick to acknowledge.

“You’re expected to treat others as you’d want to be treated, no matter what the issue is,” said Marlene Fisher, a recently retired bank manager, who explained that it’s a value that’s passed down through the generations. “It’s as much cultural as it is religious.”

Bonifas “feels unbearable anxiety being in the midst of a congregation,” Father Dorn said regarding Frank’s reluctance to attend Mass. “Therefore, for pastoral reasons, he can be considered one of the homebound, who are dispensed of their obligation to go to holy Mass on Sunday due to illness, yet who watch the holy Mass on television, later receiving the holy Communion from a priest, deacon or extraordinary minister of holy Communion.”

One might assume Bonifas has forgiven everyone their transgressions for all the horrible things they’ve said and done for the things he hasn’t been able to control due to his Tourette’s. He’s a good Catholic; forgiveness is central to his faith, right?

It’s not that easy. It’s been a long, rough road.

“I’m getting bitterness completely out of my head,” he said. “It might take six months, it might take six years. … It might be hard, but I know it will be healthier for me. I can’t spend all my time being bitter. The only thing bitterness can do for me is eat me up.

“A priest is going to have a Mass for me every Thursday for six months … people are going to be praying for me. One priest told me, ‘If I had your life, I’d be bitter, too.’ … But I can’t be a sourpuss. I can’t end up at the seat of Judgment, with almighty God saying, ‘How come you ended your life being so bitter?’

“So I’m working on it.”