Celebrating Life with Mary & Elizabeth

In a visually saturated world, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed and become desensitized to beauty. Visio Divina, Latin for “divine seeing,” encourages us to slow down and engage in visual contemplation, using art as a profound tool for connecting with the Divine.

A Guide to Visio Divina

Begin by making the sign of the cross and inviting the Holy Spirit to guide your contemplation. Spend a moment meditating on the image, The Visitation Panel from the Middle Rhine polyptych Altarpiece (1405-1414) by an unknown German artist. Then, read Luke 1:36-56.

The Visitation Panel is a Eurocentric tempera painting on wood, inspired by Byzantine icons. It features elongated forms, two- dimensionality, gold leafing, inscription and sacred symbolism.

Part of the Early Renaissance, it reflects a growing understanding of naturalism and linear perspective.

Enter In.

After hearing from the Angel Gabriel about Elizabeth’s pregnancy, Mary hurries to meet her. In this panel, Mary arrives in Judah hill country, but instead of entering Zechariah’s house as Luke describes, the artist depicts their visit in a teeming garden. Why? It could suggest Mary as the New Eve or emphasize a scene of fertility that contrasts with Elizabeth’s past struggle to conceive.

To the right, a doorway with a dog—a Greco-Roman symbol of fidelity—leads into Elizabeth’s home. Above the door, an inscription reads “City of Judah.” To the left, white lilies bloom, communicating joy, new life and Mary’s purity. In the foreground right, a small stream of water alludes to the waters of Baptism.

In the center, a large rock emerges, with angels sweetly peeking from behind. The mountain image symbolizes the nearness of God the Father. Many significant spiritual encounters with the Father occurred on mountains, such as Moses receiving the Ten Commandments and the Sacrifice of Isaac. At the peak, a Latin inscription reads, “Glory to God in the Highest.” Just below, the Holy Spirit descends as a dove breathing upon the group. And, inside Mary’s womb, Jesus is depicted, the presence of the Trinity.

Mary is adorned with a crown and clothed in her traditional colors of blue and pink—symbolizing her purity and royalty. She greets Elizabeth, who wears a shroud and is dressed in red and gray, reflecting her matronly status. Scrolls gracefully unravel around the two women: around Mary are the words rom the Magnificat, “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior” (Lk. 1:46–47); and around Elizabeth, “And why is this granted to me that the mother of my Lord should come to me?” (Lk. 1:43).

Luke describes the Visitation as an incredible moment filled with joy and celebration; however, the artist here captures it with a complex depth of emotion. Notice the women’s faces: do they seem joyful? Mary gazes downward, her eyes avoiding Elizabeth’s. Though she appears calm, her expression is subtly tinged with pain and sadness. Why might this be? This may foreshadow the eventual sorrow of losing her Son, aligning with the Protoevangelium, or the “first gospel” (Gn. 3:15), which prophesizes that a Savior will come, but with much suffering. Elizabeth, gently embracing Mary, is humbled, and her expression communicates a sense of trusting awareness for the future of both of their sons.

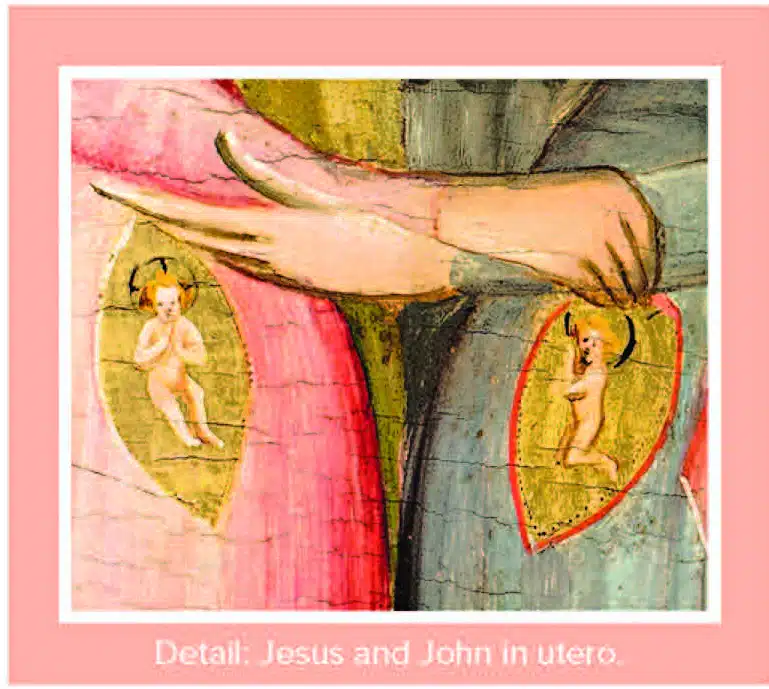

One of the painting’s most striking details is how the cousins, Jesus and John the Baptist, are charmingly depicted in utero. Filled with the Holy Spirit, John joyfully leaps to his knees in Elizabeth’s womb at the presence of the Lord. It’s fascinating that medieval society showed a deep understanding of life present in the womb, even without today’s ultrasound technology.

Pope St. John Paul II offers a profound insight into the Visitation: “When,

at the Visitation, she [Mary] bore in her womb the Word made flesh, she became in some way a ‘tabernacle’—the first ‘tabernacle’ in history—in which the Son of God… allowed himself to be adored by Elizabeth, radiating his light through the eyes and voice of Mary” (Ecclesia de Eucharistia, 55). Through its rich symbolism and exquisite depiction, this painting invites us to recognize and celebrate the sanctity of unborn life. By presenting Mary as the first to carry Jesus as a living tabernacle and proclaim the Good News, the artist calls us to follow her example, reminding us that when we receive the Eucharist, we too are called to carry Christ and share His message. As beautifully described by Nate Hile in an interview with art historian Matthew Milliner, “We must also become a womb in which the Son of God is gestated within us; so we are equally called to imitate Mary” (Matthew Milliner on The Mother of the Lamb, Grail Country).

Emma Cassani is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph. She is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith. | [email protected]

Emma Cassani is the graphic designer behind The Catholic Telegraph. She is passionate about exploring the intersection between art and faith. | [email protected]

This article appeared in the October 2024 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.