Building Habits of Virtue During Lent

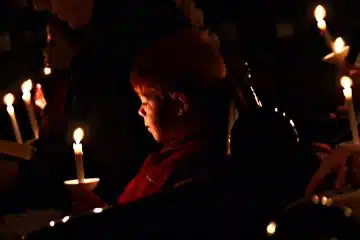

Lent is a season of moral and spiritual growth. For some, the principal approach is to deprive oneself of non-essential goods; we give up some pleasure or luxury. Others observe Lent by performing spiritual or corporal works of mercy; we add some activity or assume some burden. And, of course, many of us practice the discipline of Lent through a combination of these approaches. Regardless of the things we give up or add, however, our Lenten discipline is only effective if it is properly ordered toward the good of developing our spiritual and moral lives.

The Catholic moral life is built upon the fundamental reality that we humans are ordered toward love of God. The quest of Catholic moral theology is not what we should or should not do, but rather what kind of people we should be. Thus, we do not emphasize rules, commands or laws as such. Instead, we concentrate on the practices and habits that make us the kinds of people who obey the rules, commands and laws. Simply put, Catholic moral theology is primarily concerned with who we are, not what we do. Doing the right thing does not make a person good. But a good person, by definition, will do the right thing.

This means that Lenten practices are not ends in themselves. Rather, they are the means by which we become persons whose lives are ordered toward the natural good of life in a peaceful community and the supernatural good of rest in God. As such, Lenten disciplines are moral actions. Or, at least, they can be moral actions if they are properly considered. In the Catholic tradition, three elements must be met for a human action to be a moral action: the object, the intention and the circumstance.

The object of a moral action is the most difficult to define. In theological parlance, the object specifies the act. In the words of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, “the object … is a good toward which the will deliberately directs itself. It is the matter of a human act” (CCC 1751). In other words, the object of a moral action is the good that the person hopes to achieve by engaging in the action. Thus, the object is the specific purpose of some otherwise general action. For example, let’s say that two different people hit another person on the back. That is a general action, but we do not know what specific good either person hopes to achieve. The first may wish to congratulate his friend on making a good speech. In that case, the moral object is good. The second may desire to cause an enemy harm. That, of course, is an evil moral action. This tells us that some general actions may or may not be ordered toward the good, depending on the will of the actor.

But this is not the case with all general objects. Some moral objects can never be directed toward the true good. For example, euthanasia and elective abortion or sterilization (as opposed to indirect sterilization caused by a necessary medical procedure) are moral objects that serve no general human good. They specify a will that is contrary to both the natural and supernatural goods of the human person. We sometimes call these objects “intrinsically evil.” I prefer the phrase “inherently disordered” because it indicates why these objects are prohibited: they do not order the human person toward his or her true good.

The second element of a moral action is the intention of the moral agent. Intentionality names the purpose of choosing a moral object. If the intention is not good, neither can the moral act be, even if the object is one that could be ordered toward the good. For example, if I give a large donation to a charity with the intention of furthering its mission, that would fulfill the intention element. But if I make that donation with the intention of seeing my name on the building or because I expect some benefit in return, the potentially good moral object of charity becomes a bad moral object of self-aggrandizement.

But it doesn’t work the other way around. Intention may cause a potentially good moral object to contribute to a bad moral action. But it can never cause an inherently disordered moral object to contribute to a good moral action. As an example, no motive, regardless of how noble the actor thinks it is, can order abortion toward a human good. Intention can ruin a good moral object, but it can never save a bad one.

Finally, if the object is good and the intention proper, a moral action must also consider the circumstance in which it is exercised. From the Latin for “stand around,” the “circumstance” of a moral action may alter the relative goodness of the act. It may make the action more or less blameworthy or praiseworthy. For example, yelling “Fire” in a crowded theater is a good moral action if there is, in fact, a fire. But if there is no fire, that circumstance changes the moral action to a blameworthy one, as it will cause panic and possibly injury to the patrons.

What has all this to do with Lent? When we consider our Lenten disciplines, it is crucial that we analyze our actions (or abstinence) through these three elements. If any of the three are missing or defective, we are not going to achieve our purpose of spiritual and moral growth. A moral action requires a good (or potentially good) object, the proper intention and the right circumstance. When these conditions are met, it will be a fruitful Lent with lasting consequences.

Dr. Kenneth Craycraft holds the James J. Gardner Chair of Moral Theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology. He is the author of Citizens Yet Strangers: Living Authentically Catholic in a Divided America.

Dr. Kenneth Craycraft holds the James J. Gardner Chair of Moral Theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology. He is the author of Citizens Yet Strangers: Living Authentically Catholic in a Divided America.

This article appeared in the March 2025 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.