Priests share hope for new Pittsburgh parish in Black Catholic tradition

by Kate Veik

Denver Newsroom, Mar 13, 2021 / 02:00 am MT (CNA).- Last summer, Bishop David Zubik of Pittsburgh made an important announcement. St. Benedict the Moor, a historic parish in the Hill District near downtown Pittsburgh, would become a personal parish in the Black Catholic tradition.

Most parishes are territorial, meaning they’re built around geographic boundaries. Personal parishes are built around a particular tradition.

The announcement came in the midst of nationwide protests against systemic racism. In an interview following the announcement, Bishop Zubik said the timing wasn’t intentional— it was providential. The diocese and parishioners at St. Benedict had been in communication since the beginning of the year, and St. Benedict the Moor parish has a long-standing history of ministry to Black Catholics in Pittsburgh.

“The parish was founded on July 28th, 1889, by priests of the Congregation of, what was then, the Congregation of the Holy Ghost, which is now the Congregation of the Holy Spirit,” said Ken White, a former archivist for the diocese of Pittsburgh.

White told CNA a priest with the Congregation was interested in starting a mission in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. The Hill District today is predominantly African American. And it was the same back then.

The priest held a series of meetings to see if there would be support for a parish in the Hill District.

“He was assisted with that by three local black Catholic ladies – Elizabeth Anderson, Fanny Brent and Mrs. Lloyd Thomas,” White said. “After their meetings, in 1889, Fr. McDermott rented a mansion on Fulton street and …it was converted to a combination church and school, which again was dedicated on…July 28th, 1889.”

St. Benedict wasn’t the first Black Catholic parish in the city. The first was called Nativity, and it was established in 1844 in downtown Pittsburgh. But Nativity closed after one year. The second was St. Joseph, founded in the Hill District in 1866, but White said the parish closed within three years because of the aftershocks of the Panic of 1873.

St. Benedict Parish, on the other hand, flourished. Within two years of its founding, the parish was able to purchase a plot of land, and build a new church and school. The parish went on to serve the Hill District community for nearly eight decades.

During that time, the population of the Hill District plummeted from more than 53,000 in 1950 to 29,000 by 1978. Entire blocks of the neighborhood were torn down to make room for a new Civic Arena. The Hill District and St. Benedict parish fell into disrepair.

“A lot of it was urban renewal,” White said. “Of course, part of it too was people moving out of the city. The city has been having a pretty steady decline in population. That goes back to the collapse of the steel industry, but I’d say for the Hill District itself, it was mostly urban renewal.”

St. Benedict’s original church was torn down, and from 1968 to 1977, the parish went through a series of mergers – eventually settling into the church of a formerly German parish in the Hill District.

Up until its designation as a personal parish in 2020, Saint Benedict was a territorial parish. But it was always informally known as Pittsburgh’s Black Catholic parish.

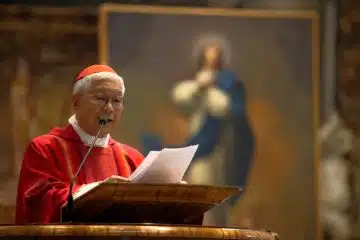

“It was always considered, at least in my time, the African-American parish in the Diocese of Pittsburgh,” said Father David Taylor, senior parochial vicar at St. Benedict.

Taylor was first introduced to St. Benedict back in the 1970s, when his brother was pastor. The parish was known for its music, preaching, and community life.

“In the past, they were, for all intents and purposes, they were a personal parish for African-Americans, which didn’t mean that the only parish African-Americans could attend was St. Ben’s, or that if you weren’t African American, that you could not attend. That wasn’t what it was, but there was a good cultural fit,” said Father Matthew Hawkins, parochial vicar at St. Benedict.

Hawkins first became acquainted with St. Benedict in the 1990s, as a parishioner. He said the parish was thriving in those days.

“The parish was proactive in making a connection between scripture studies, what was going on in the liturgy, and the day-to-day lives of people in African-American communities,” Hawkins said.

Both Taylor and Hawkins said St. Benedict’s official designation as a personal parish will help the parish better evangelize the Hill District and the greater Pittsburgh area.

One way they hope to meet that goal is by offering more Masses. The parish is offering limited Masses right now, because of the coronavirus pandemic. Hawkins said the more Masses they can offer, the better they can accommodate the diversity of the Black community.

“It’s not a monolith, it’s not a single thing. There’s diversity within the African-American community,” Hawkins said. “That demographic diversity of some people being the children of recent immigrants from either Africa [or] the Caribbean and some people being legacy African Americans.”

Hawkins said there are also cultural and socioeconomic differences.

“The Black middle-class and the Black working class, and those who were unemployed frequently see things sometimes very differently,” Hawkins “It’s important to be able to speak to those experiences.”

“If a parish isn’t aware of those nuances, it’s hard to meet those needs.”

St. Benedict is a personal parish in the Black Catholic tradition, but that doesn’t mean it’s closed off to other Catholics.

“Even though it’s a personal parish of African-Americans, there are many white members who belong to it because they love to worship there and the friendship and social change that goes on there,” Taylor said.

But St. Benedict is tailored to the needs and the realities of Black Catholics.

“Too often, people of African descent will look at the Catholic Church and say that all the images they see and all the references to Sacred Scripture don’t seem to resonate with their experiences. I think that’s a fair charge – it doesn’t have to be that way,” Hawkins said.

“In terms of speaking to the spirituality of African-Americans, there are certain texts within Sacred Scripture that resonate more…with the Black community than perhaps with other communities.”

For example, the passion of Christ may resonate with the experience of loss and suffering in distressed neighborhoods.

“Of course not all Black Catholics, and probably not even the majority, necessarily live in distressed neighborhoods,” Hawkins said. “But the connection between the passion of Christ and how that is seen through the lens of the neighborhood is important in terms of our ministry. Because ours is … a faith that focuses on the Incarnation. People have to see themselves in very tangible ways and very physical, embodied ways in order for it to have deep meaning for them.”

Hawkins said other parts of scripture also resonate with the Black Catholic community.

“What is the parallel between the Psalms of Lamentation and the Blues,” he said. “What is the significance of the book of Exodus to the African-American experience or the prophet Amos and his proclaiming the importance of justice? What is the significance of the Gospel of Luke? Why does that resonate particularly well, that particular Gospel, which focuses on bringing in the outsider and the marginalized and so forth?”

“All of those are areas that people who are administering to African American communities should be aware of.”

Hawkins said it’s also important to consider the role of historically Black Protestant tradition churches in Black neighborhoods. The relationship between the two dates back to before the Civil War, when there were many efforts to evangelize people who were enslaved. A lot of that evangelization was done by Methodists, Baptists and Presbyterians.

When the Civil War happened, virtually every Protestant denomination split over the question of what to do about members of the congregation who were also slave owners.

“After the Civil War, some of the churches came back together, some of them remained separated. But there was a new initiative to say, we don’t want Blacks and whites to worship together,” said Cheryl Sanders, a professor of Christian ethics at Howard University’s School of Divinity in Washington and senior pastor of Third Street Church of God.

The separation of worship led to the creation of Black denominations within Protestant traditions.

“You have separate denominations that mirror the same teaching and discipline and policy of the white denomination,” Sanders said. The reason for this is that “we’re Black and white, and we can’t worship together. And when I say ‘we,’ it’s essentially the white initiative to say, we do not welcome Blacks into our worship.”

“Then of course, all along, you have, Blacks in Catholicism. But the Protestant ethos remains dominant in the African-American community.”

Sanders said this remains true even today.

“In a Black community, if you ask, ‘Who are the leaders?’ ‘Who are the spokespersons?’ ‘Who are the people who are leading in social justice?’ You can’t overlook the black preachers,” she said.

Historically Black Protestant churches have had such an impact on Black communities, Sanders said, because Black churches formed in response to rejection from the white churches.

“The white church … They are not the dominant factor in the life-giving livelihood of the community because the white church sees itself as this almost a seamless entity with the political structure, economic structure,” Sanders said.

“In other words, in a white-dominated society, the church does not have the same role that the church has in the black society, where the black people, under conditions of oppression, living in the consequences of shadow white supremacy, the black church becomes the spokesperson. It becomes the resource, it becomes the property owner. It becomes the help,” she said. “A people living under circumstances of oppression look to the church in ways that people in the dominant culture would never even think to look to the church for that kind of leadership or that kind of help.”

The Catholic Church can’t replicate the influence of historically Black Protestant traditions on Black communities in the U.S., but Hawkins said there are some best practices he hopes to adopt at St. Benedict parish in Pittsburgh.

One of those best practices is providing role models at the parish for young parishioners.

“I think people will find, if they look at the historically black Protestant tradition churches and ask why they’ve been so strong in the past, fundamental to that was the parents knew that if they brought their children there, your children could see themselves in those who were responsible for ministry,” Hawkins said. “They could see themselves and they could see examples of an alternative to a lifestyle that treats people as disposable objects, or treats people as objects for entertainment. It really provides a viable alternative. It’s important for the Catholic Church to provide that.”

“And this is where we obviously have a need for more African American priests and deacons.”

Taylor was the first Black Catholic priest ordained in the Diocese of Pittsburgh, in 1974. He was the only Black Catholic priest in the diocese until 2020, when Hawkins was ordained.

“That’s been probably one of the biggest disappointments to me because I had really hoped, since I was making inroads here, there would be many, many other vocations,” Taylor said.

Both Taylor and Hawkins are converts to Catholicism. Taylor comes from a long line of Baptists and Episcopalians. His immediate family converted because of their experience with Catholic education.

“My parents had always wanted to send us to Catholic schools from the earliest point,” Taylor said. “When I was first coming up, the schools in Kentucky were segregated and not very good for African-American children.”

His family moved to Cincinnati when he was about five or six years old, and his parents enrolled him and his siblings in Catholic schools.

“And although, [there] was a lot of racism, even within the Catholic Church and schools, the value of having the Christian Catholic education meant a lot,” he said. “That was the immediate catalyst of us coming to the Catholic Church.”

Hawkins is the son of an African Methodist Episcopal minister. His mother was Baptist. Like Taylor, Hawkins attended a Catholic elementary school and his experience led him to convert to Catholicism at the age of 21. He wouldn’t become a priest until several decades later, after earning master’s degrees in social work and applied history, and working for 20 years as an educator and in community economic development.

Hawkins said historically Black Protestant Churches are also heavily involved in the communities that surround them. He hopes to emulate that at St. Benedict parish.

“It’s going to be important, even though St. Ben’s is seen as a personal parish, rather than a geographical one, for us to be very present in the surrounding community, which is a predominantly African-American community,” Hawkins said.

He said this community engagement means building personal relationships.

“It’s not just attending meetings, and it’s not just checking off the boxes. It is really building real relationships with people in the neighborhood and then the community,” he said. “Catholic and non-Catholic.”

Community engagement also provides opportunities for evangelization. Hawkins said evangelization can sometimes be as simple as talking about prayer.

“I don’t think the first sell is going to be on questions of doctrine. I think you get there later,” Hawkins said. “What everybody understands and what’s easy for people to appreciate is prayer life. When you offer people more vehicles to have a richer spiritual life, a richer prayer life, people appreciate that.”

“Even those things that we think of as being almost exclusively Catholic and we think that it wouldn’t connect with other people, such as the rosary,” he said. “You will notice in the inner city that a lot of young people have rosaries. I know people will criticize how they use them, they’ll wear around their necks for decorative purposes. But if you talk with a lot of young people who are not Catholic, who have acquired these rosaries, they’ll get it that there’s a spiritual connection, that they experience something where they feel protected, where they feel connected with the source of their being, with the origins of their creation…There’s not a big leap between wearing a rosary and praying the rosary.”

Many of Taylor and Hawkin’s plans for St. Benedict parish are on hold because of the coronavirus pandemic. But the priests said they hope St. Benedict will enrich the Diocese of Pittsburgh, and the Church in the United States.

“A lot of the divisions we have in our society today, they might be expressed in mean-spirited ways, but they frequently don’t come from mean-spirited people. They come from people who are afraid,” Hawkins said. “Part of breaking down that fear is when people actually get to encounter each other as human beings and know each other as human beings and move beyond the one-dimensional stereotypes on all sides.”

“That’s, I think in many ways, what is essential to deepen the catholicity of the Church and to deepen that Catholic experience of the Church,” he said.

“When people come to visit St. Benedict the Moor from other parishes, usually when you talk with them, that’s why they come. That’s why they bring their families. Because they want their children to have the experience of a liturgy that wakes them up. It’s different from how the liturgy is celebrated in maybe their home parish … and to begin to see the diverse ways in which we can express the joy of the Eucharist in a single city…That’s definitely something that African-American communities can bring to the Catholic Church.”