Application and Evaluation Precedes Seminary Acceptance

By John Stegeman

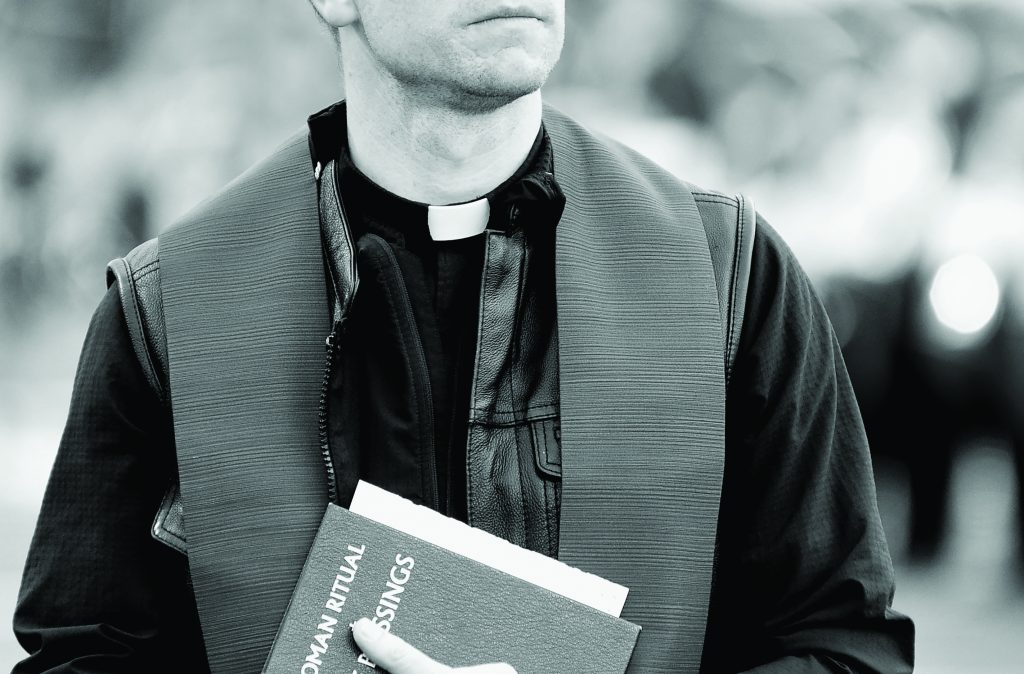

Becoming a diocesan priest is a calling that must be discerned by both the individual and a diocese If a student is accepted into seminary, he will have five to nine years of formation before priestly ordination. Even before that, however, an intensive process takes place designed to help men discern their call, and to redirect those who do not have an authentic vocation to the priesthood.

Father Dan Schmitmeyer is the current gatekeeper. As the Archdiocese of Cincinnati’s director of vocations, he meets with men who feel called to the priesthood and guides them through the vetting and application processes.

It begins when a potential applicant reaches out and shares that he is discerning a call to priesthood. Father Schmitmeyer meets with him (and the his parents, if he is of high school age) two to three times, discussing a wide range of topics.

“I talk about their family, their dating history, sexual relationships… all of those types of things,” Father Schmitmeyer said. “If it’s obvious they’re not living what the Church teaches, and they’re promoting a lifestyle that isn’t following Church teaching, that’s pretty much going to stop the process. Sometimes you know this isn’t going to work. Others I’ll work with for several years. They’ll go to a spiritual director and spend time meeting with them to get into a good relationship with Jesus.”

If the man passes muster, the application begins in earnest. It includes an eight-hour psychological evaluation, a six- to eight-page autobiography, criminal background check and a review of educational transcripts and sacramental records.

Every year, said Father Schmitmeyer, several applicants are turned away. The pressing need for new priests has no bearing on the application process. The archdiocese is looking for well-adjusted men who can become good and holy diocesan priests. If it seems like someone isn’t called to that kind of life, they will be told so.

“Sometimes, even after a year or two in the seminary, or more, the diocese or seminary may say, ‘This isn’t for you,’” he said. “We want you to go to heaven and live a joy-filled life.’ This may not lead you there.”

Discerning a call to ordination, even if it doesn’t lead to acceptance as an applicant, is still worthwhile for those seeking to do God’s will. Father Schmitmeyer said some men are even relieved when they are dismissed from consideration, as it frees them to discern their true vocations, like marriage or consecrated life.

“Some men are not called to diocesan priesthood,” Father Schmitmeyer said. “That doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with them.”

One important component of the application is psychological testing. The archdiocese uses Ruah Woods, a Theology of the Body education center in Cincinnati, to perform the evaluations. There are no national or international standards a diocese must follow in having potential applicants evaluated, leaving the decision up to each diocese.

“I’ve talked to the rectors of other seminaries, and they say they love what Ruah Woods does because it is so thorough,” Father Schmitmeyer said. “They get into everything.”

“We take these evaluations very seriously and try to use a thorough and multifaceted approach,” said Dr. Andrew Sodergren, a clinical psychologist at Ruah Woods. “Our role is to gather information that may not be available to the diocese, religious order or seminary through other means. We’re expert consultants hired on to gather information of a psychological nature on these candidates.”

Sodergren said the evaluation, which was designed at Ruah Woods with an eye toward one day creating a national standard procedure, looks at the whole person, even things they may wish to hide.

“We assume that everyone who goes through this is motivated to conceal things,” he said. “I’m not trying to say they have bad intentions, but as a candidate applying to a seminary, it puts them in a position where they are naturally motivated to put their best foot forward and to minimize or conceal any wounds, weaknesses or problems they might have. Our approach takes that into account.

“People who commit boundary violations or otherwise seriously harmful behavior typically carry multiple signs of poor psychological health,” Sodergren added. “There may be signs of addiction, problems with empathy, problems with authority, personality disorders, emotional problems, etc. So, we look at the whole picture and try to provide a robust glimpse at this person’s psychological make-up.”

If, after meeting the applicant and going through the process, a man is accepted by the archdiocese, that still isn’t the end of his journey. A seminary must review the information and determine whether it will accept him. A letter of recommendation from Father Schmitmeyer factors into the decision. At some seminaries, including Mount St. Mary’s Seminary of the West, this includes additional interviews. Sodergren said sometimes a seminary or religious community will order a second round of psychological testing.

First contact with Father Schmitmeyer to acceptance into seminary can take anywhere from six to eight months.

Once an applicant is in the seminary, evaluations continue. Each year, the seminaries send an evaluation of each man to his diocese for review. At any step in the process, the diocese or seminarian may discern a man is not called to continue.

According to Father Anthony Brausch, rector of Mount St. Mary’s Seminary, “We regularly evaluate each seminarian’s disposition, behavior, self-awareness, and stability and goodness of character. When a man discerns that God might be calling him to the priesthood, the Church has a duty to discern that call as well, to make sure he is truly called and of the right character to serve faithfully and well.”