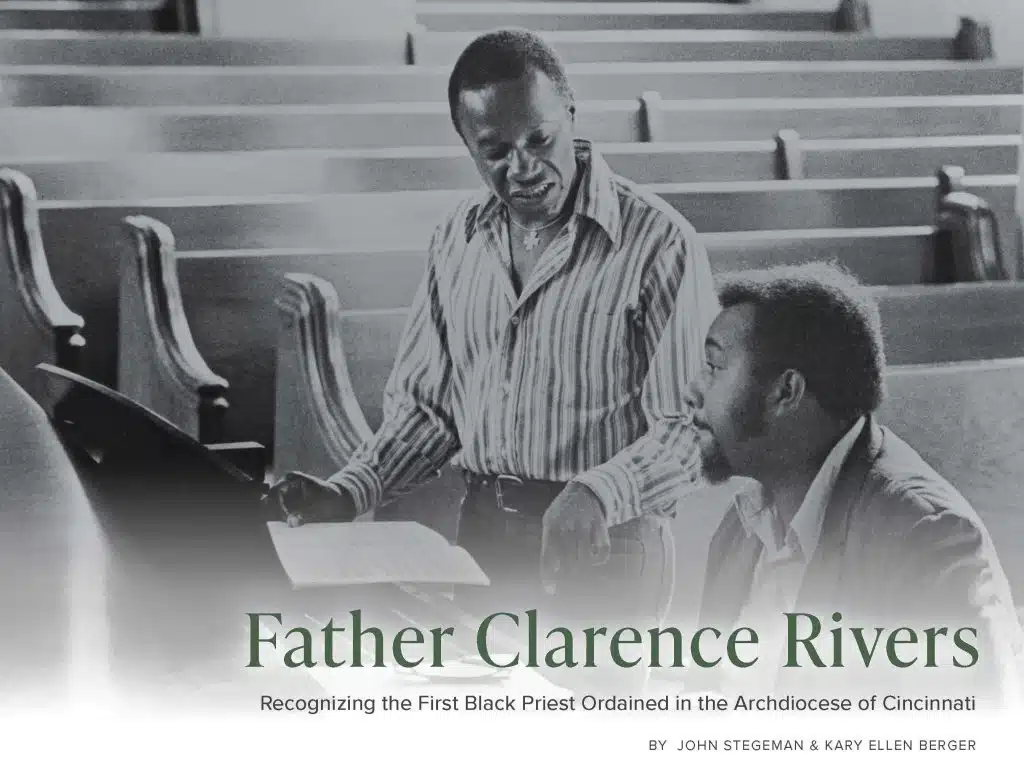

Father Clarence J. Rivers

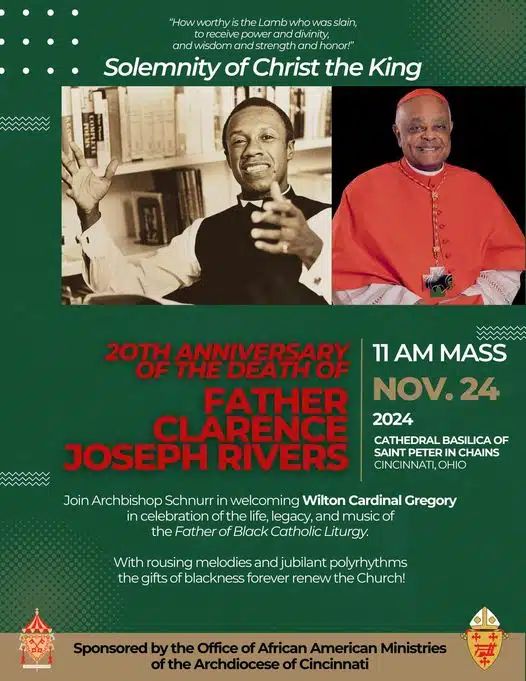

Father Clarence J. Rivers was the first Black priest ordained in the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. A nationally known figure in Catholic music and liturgy, he was also an iconic figure for the Black Catholic community throughout the country. Although he died in 2004, his influence is still felt throughout the archdiocese and beyond.

“When Black Catholics around the United States reflect on the inculturation of Black spirituality [music, art, movement, prayer and faith], Father Rivers is the name that rises to the top,” said Deacon Royce Winters, Director of African American Pastoral Ministries for the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. “The local

Black Catholic communities in the U.S. and in this archdiocese have continued to carry on the legacy of inculturation which began with Father Rivers.”

Born in Selma, AL, Father Rivers moved with his family to Cincinnati when he was young. After attending St. Gregory and Mount St. Mary’s Seminaries, he made history in 1956 as the first African American priest ordained in the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. Assigned as associate pastor at St. Joseph’s in Cincinnati’s West End, he taught at Purcell High School and later served at Assumption in Walnut Hills. In 1965, the archdiocese released him from his assignments to pursue his program of inculturation of African American culture in Catholic worship.

Using his gifts in music and liturgy, Father Rivers introduced African American spiritual tradition elements into Catholic worship, creating a more inclusive and meaningful experience for all. He also became well-known as a liturgical artist, composer and author. “God is Love,” possibly his best-known hymn, was sung at the 1964 National Liturgical Conference during the first High Mass said in English in the U.S. Catholic Church—the assembly applauded for 10 minutes after it was sung.

Father Rivers’ influence extended beyond music as his writings emphasized the importance of recognizing and celebrating cultural diversity within the Church. His efforts paved the way for what we now recognize as contemporary Black Catholic liturgy, encouraging the Church to embrace the richness of diverse expressions of faith.

In a 1977 article in The Catholic Telegraph, Father Rivers said that to some people the Church “is one big happy family and any giving in to ethnic concerns is wrong. To them there is one faith, one Baptism, one Church and one culture—namely European.”

Deacon Winters calls Father Rivers a friend and mentor, and he feels Father Rivers’ legacy in his current ministry.

“In 1978, as my family and I searched for a church home, we attended St. Agnes Church,” Deacon Winters said. “Father Rivers was serving as the guest homilist and he preached about racial injustice. I spoke to him afterwards because I was disturbed about his message. I was seeking Christ, and he was preaching about racial injustice. [He] invited me to his home, and we began a lasting friendship. After my deacon ordination, he would often call me and say, ‘I need my deacon.’ I would accompany him to various dioceses for liturgical services and workshops, serving as his deacon and cantor. Father Rivers was instrumental in my liturgical formation and the freedom to embrace the culture of being authentically Black and Catholic.”

“Although small in physical stature, he had a presence that was larger than life,” said Father Rivers’ sister in his obituary in the Cincinnati Enquirer. “Once he entered a room or a gathering, you knew you were in the midst of someone extraordinary.”

Father Clarence Rivers was a pioneer in the Church, particularly for his work in bringing African American culture into Catholic liturgy; and this year is the 20th anniversary of his death.

“On August 9, we were awarded a historical marker for Father Rivers by the Ohio Historical Connection,” said Deacon Winters. “It is our hope that prior to Mass [on the Feast of Christ the King] on November 24 … [visiting] Cardinal Gregory will lead the pilgrimage to St. Joseph Catholic Church, the first church of Father Rivers, to bless the permanent grounds of the historical marker.”

This article appeared in the November 2024 edition of The Catholic Telegraph Magazine. For your complimentary subscription, click here.